.jpg)

.jpg)

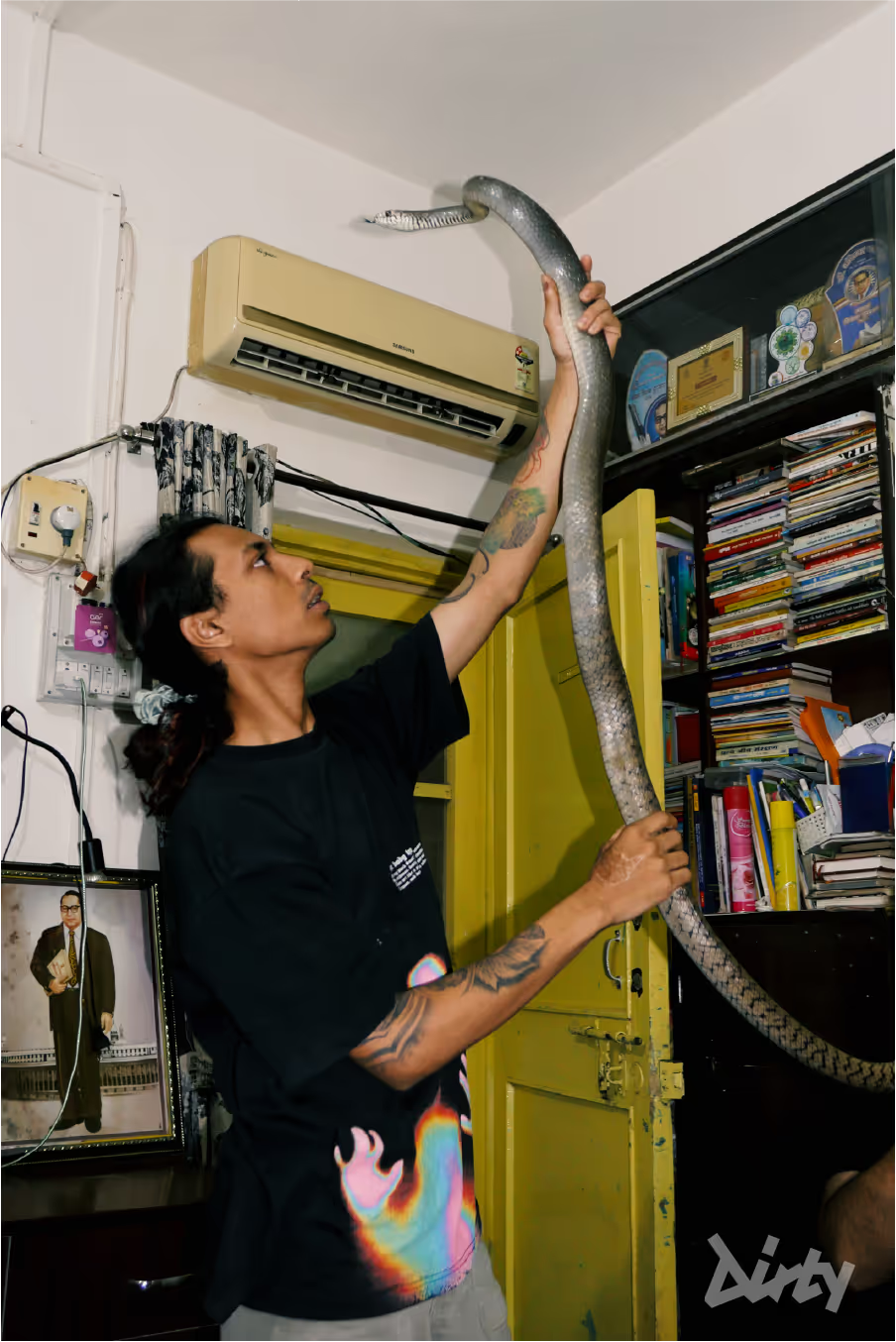

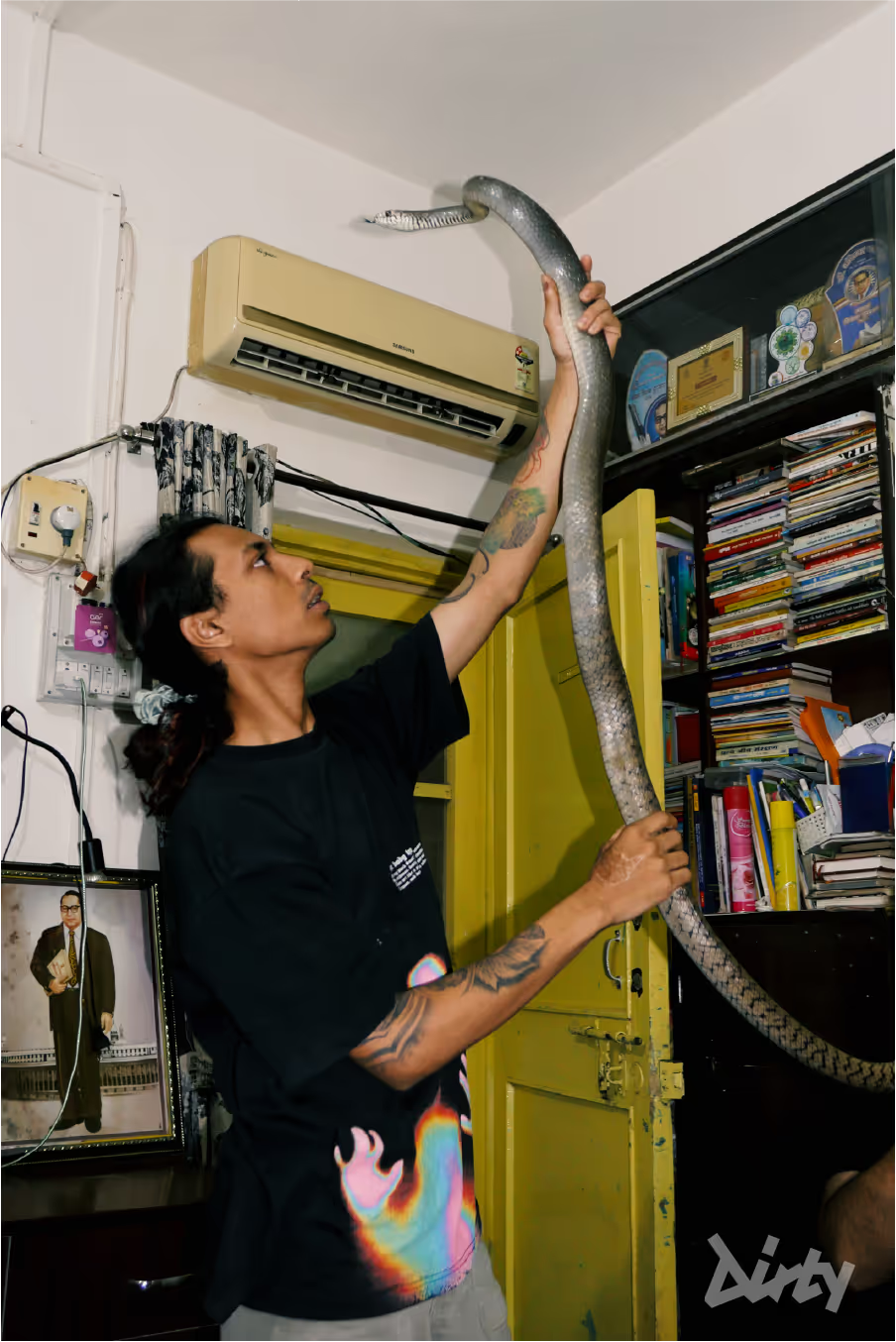

<h1 class="left">I dreamt of snakes the night I met Abhirup Kadam. Not the terrifying kind I’d spent my life avoiding, but intelligent, beautiful creatures — coiled, calm, and oddly familiar. Kadam, a wildlife rescuer and content creator with over one million subscribers on Youtube, moves through the city with a calm that makes even the most feared animals seem almost familiar.</h1>

<h1 class="left">Late one night, knee deep in the Instagram hole, I stumbled across one of his reels, which led to another, and then hours of watching his rescue vlogs — him pulling snakes from tiny crevices and bathroom drains, always careful, always speaking gently to the excited crowds that form around him.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">Something about the way he worked — focused, fearless, and deeply respectful of the creatures he handled — pulled me in. I had to reach out and unearth this individual’s penchant for putting his life at risk to save reptiles. And before I knew it, I was following him across Mumbai, watching these rescues unfold in real life. That’s how I ended up at Thane Creek — just four feet from a spectacled cobra, heart racing.</h1>

<h1 class="right">When I reached the MARA field office (Maharashtra Animal Rescue Association) in Chembur, my Uber trip ended at the entrance of a wedding hall. White curtains, fake roses and green plastic jewels decorated the facade. Not what you’d consider a typical hunting ground for snakes. Kadam pulls up on his bike so that I can hop on for a grand tour of the RCF colony, which is where we will be documenting his rescues for the next few days. We whizzed past giant playgrounds, a sports centre, a hospital, schools, and a nursery— all of which were also home to a sizeable snake population.</h1>

<h1 class="right">As we return home from this recce, his mom makes us chai while we wait in his living room for a rescue call and play with his pets— rescued iguanas lounging in the living room.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">I notice a giant scar on Kadam’s hand as he sips tea; he was bitten by a cobra right before his 12th board examination. He was called one night around two AM to rescue a six-foot-long cobra from someone's house. A man residing in the same area offered to help him by holding the torch, but as soon as the snake hissed, he dropped the torch and ran. “At first you feel like you’ve guzzled a litre of the strongest whiskey available,” says Kadam, explaining that as the minutes go by, the drunken dizziness makes your tongue heavy and your eyesight starts to dwindle. “I knew that if I closed my eyes, I’d be gone.” His mother was concerned, of course, about his hand, since he needed to write his paper. He was finally administered the antivenom three hours later, but had to get a skin graft from the necrotic tissue on his hand.</h1>

<h1 class="left">While we patiently await a call in the hot summer afternoon, Kadam casually opens a box which is a temporary home to a cobra who needs to be released back into the wild. He picks up the snake and places it into his backpack, as we decide to take it back into its habitat. We drive into a camouflaged lane off the highway, past an influencer doing an illegal photoshoot, past acres of dried-out salt pans, then some salt pans with a little water that had all the birds basking in the heat, till we reach a hidden alcove fashioned out of unruly bushes. He places his bag down and opens the zip. Hesitant at first, the cobra slowly exits the bag one inch at a time and immediately turns to face Kadam, who is holding him gently by the tip of his tail.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">To my dismay, I have let out an unprofessional squeal at this sight. Kadam tells me not to worry (which I most certainly still do). I tried to record a video, but my hands were shaking too much. The snake apparently won’t slither away into the bushes because it seems to be waiting for an attack from his captors, Kadam tells me. We don’t know this for sure, but the ease with which Kadam handles the snake instils this blind, and foolhardy faith in his statement. He talks to me about boundaries and how if he respects those, the snake won’t bite him. He walks in circles around the snake to demonstrate how it mimics his movement in perfect rhythm..</h1>

<h1 class="right">Then, Kadam crouches in front of the snake and appears to be having a conversation. While the pair remain interlocked in this trans-like moment with the snake, till eventually, it decides that it’s safe enough to slither away into the safety of a shrub.</h1>

<h1 class="right">I dreamt of snakes that night.</h1>

<h1 class="right">On the second day of my documentation process, I arrive at Kadam’s house and am met with his extended family, which consists of some domestic and other not-quite-domesticated animals residing at his home. In cages outside and inside the house are the animals they have rescued, who need some more ‘laad pyaar’ as his mom says before they can be let go. Some have been abandoned and have been adopted by the family. His dad is leaving to teach young kids about animal awareness. He takes some of the pocket-sized companions — a rabbit, a fluffy cat, some small colourful birds, loud ducks, and the iguana named Charizard with him.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">I’m walking around to observe the ducks in his backyard when I step on the shedded skin of a rattlesnake and I immediately scurry back inside. There’s a lull in the rescue operations these days, where Kadam would usually receive 20 calls a day from the concrete jungle that is Mumbai, it seems to be dwindling.. A few months ago, when the construction of Atal Setu was still underway, he would get multiple calls for snakes due to the destruction of the animal ecosystem in the area. Some even required him to get on a speedboat and rescue snakes from construction ships that were anchored deep in the ocean.</h1>

<h1 class="left">A rescue call came in this morning, just five minutes away from where we were. We reached a small building where a group of women in their morning kaftans and keds had already gathered outside, curious about the commotion. A few female gardeners in printed scarves and green jackets joined in too, trying to see what kind of snake it was.</h1>

<h1 class="left">Kadam, focused as ever, asked where it was. They all pointed upward. The mood was more excited than scared. We ran up to the first floor, and just as we reached the landing, I caught a glimpse of its tail. That’s when it hit me — why the hell was I in front?</h1>

<h1 class="left">Kadam spotted it and picked it up in one smooth motion. Despite its reputation, the snake was beautiful. All my nervous energy vanished. I forgot it was even supposed to be scary. The residents on the floor peeked out, phones out, recording videos for their WhatsApp groups.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">The snake was golden-yellow, wriggling gently in Kadam’s hands. He moved with it carefully, supporting its body. As we headed back downstairs, he paused to let everyone take photos and ask questions. He explained patiently: it wasn’t venomous, it wouldn’t bite, and it was only there looking for a sunny spot to bask in. It was mating season, he added, which is why the males were so bright in colour. This one had just shed, which gave it that shiny, almost iridescent look.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">We put it in a bucket of water to cool off. It relaxed, then curled its tail around Kadam’s wrist. He showed me where its heart was — you could actually see the scales moving with its breath. I touched it gently with one finger. I think it felt my pulse too. It started to get a bit agitated, probably because it could sense my fear. Kadam slipped it into his bag to release it somewhere quieter later.</h1>

<h1 class="right">Back at the office, his mum had made us kheema pao. She’s part of MARA and has been rescuing animals with her husband for over 30 years. She told me she used to go on snake rescues even when she was pregnant with Kadam. There’s a superstition that if a pregnant woman looks a snake in the eyes, her child will be born blind. She made it her mission to bust that myth.</h1>

<h1 class="right">At the building’s security desk, I noticed a torn poster Kadam must’ve put up ages ago — a list of venomous and non-venomous snakes. The boys told me people in Chembur don’t kill snakes anymore. They’ve created so much awareness that now everyone knows who to call and how to handle it.</h1>

<h1 class="right">Later, at home, Kadam’s mum was reading the paper. He placed a dying snake in front of her — it wasn’t going to make it. A few minutes later, it stopped moving. He placed it gently in front of the Buddha statue.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">Before we could catch a breath, another call came in — this time from HP Gas Colony. A snake was caught in the netting. The guards greeted Kadam with respect. One man asked us to follow him on his bike to the spot.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">The smell hit us first. Kadam didn’t hesitate. Someone handed him scissors, and he started cutting the net. It was a rat snake, non-venomous and common in the area. Kadam let it coil around him as he worked, unbothered.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">The snake calmed down as if it could sense his energy. Right next to it, another snake had died, trapped and rotting. The smell was awful. Birds circled overhead. It was a senseless death. Kadam cut the dead snake loose too.</h1>

<h1 class="left">A few men had gathered by then, chatting and giving their opinions. Kadam picked a pink flower and a bit of tulsi, dug a small grave, and buried the snake.</h1>

<h1 class="left">As we drove home, I felt a mix of anger, sadness, and helplessness. Kadam told me about another superstition — apparently, in the Konkan region, people believe that if a rat snake pokes you with its tail, you’ll change genders. I can confirm that’s not true. I touched the tail and still feel like myself.</h1>

<h1 class="left">Snakes are strange creatures — always slipping between myth and reality. In Mumbai, they hide in drains, gardens, schoolyards, construction sites — always close, always just out of view.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">After spending a few days with Kadam, I’m no longer paralysed by the idea of a snake slithering past my feet. But I’m also not cured of the discomfort, the inherited ickiness that still gives me goosebumps. Maybe that’s okay. We don’t need to love snakes. But we do need to learn how to live with them. And in the world he’s building — where children grow up knowing the difference between fear and respect — maybe fewer snakes will die for simply being snakes.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">Earlier that day, a snake had wrapped itself around my neck and face — I let it, to let it “read” me. Kadam stood nearby, holding its head, guiding me. He told me to breathe slowly and wrap my hand around its heart. And just like that, it relaxed. So did I.</h1>

<h1 class="left">Photography: Tia Chinai</h1>

<h1 class="full">I dreamt of snakes the night I met Abhirup Kadam. Not the terrifying kind I’d spent my life avoiding, but intelligent, beautiful creatures — coiled, calm, and oddly familiar. Kadam, a wildlife rescuer and content creator with over one million subscribers on Youtube, moves through the city with a calm that makes even the most feared animals seem almost familiar.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Late one night, knee deep in the Instagram hole, I stumbled across one of his reels, which led to another, and then hours of watching his rescue vlogs — him pulling snakes from tiny crevices and bathroom drains, always careful, always speaking gently to the excited crowds that form around him.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Something about the way he worked — focused, fearless, and deeply respectful of the creatures he handled — pulled me in. I had to reach out and unearth this individual’s penchant for putting his life at risk to save reptiles. And before I knew it, I was following him across Mumbai, watching these rescues unfold in real life. That’s how I ended up at Thane Creek — just four feet from a spectacled cobra, heart racing.</h1>

<h1 class="full">When I reached the MARA field office (Maharashtra Animal Rescue Association) in Chembur, my Uber trip ended at the entrance of a wedding hall. White curtains, fake roses and green plastic jewels decorated the facade. Not what you’d consider a typical hunting ground for snakes. Kadam pulls up on his bike so that I can hop on for a grand tour of the RCF colony, which is where we will be documenting his rescues for the next few days. We whizzed past giant playgrounds, a sports centre, a hospital, schools, and a nursery— all of which were also home to a sizeable snake population.</h1>

<h1 class="full">As we return home from this recce, his mom makes us chai while we wait in his living room for a rescue call and play with his pets— rescued iguanas lounging in the living room.</h1>

<h1 class="full">I notice a giant scar on Kadam’s hand as he sips tea; he was bitten by a cobra right before his 12th board examination. He was called one night around two AM to rescue a six-foot-long cobra from someone's house. A man residing in the same area offered to help him by holding the torch, but as soon as the snake hissed, he dropped the torch and ran. “At first you feel like you’ve guzzled a litre of the strongest whiskey available,” says Kadam, explaining that as the minutes go by, the drunken dizziness makes your tongue heavy and your eyesight starts to dwindle. “I knew that if I closed my eyes, I’d be gone.” His mother was concerned, of course, about his hand, since he needed to write his paper. He was finally administered the antivenom three hours later, but had to get a skin graft from the necrotic tissue on his hand.</h1>

<h1 class="full">While we patiently await a call in the hot summer afternoon, Kadam casually opens a box which is a temporary home to a cobra who needs to be released back into the wild. He picks up the snake and places it into his backpack, as we decide to take it back into its habitat. We drive into a camouflaged lane off the highway, past an influencer doing an illegal photoshoot, past acres of dried-out salt pans, then some salt pans with a little water that had all the birds basking in the heat, till we reach a hidden alcove fashioned out of unruly bushes. He places his bag down and opens the zip. Hesitant at first, the cobra slowly exits the bag one inch at a time and immediately turns to face Kadam, who is holding him gently by the tip of his tail.</h1>

<h1 class="full">To my dismay, I have let out an unprofessional squeal at this sight. Kadam tells me not to worry (which I most certainly still do). I tried to record a video, but my hands were shaking too much. The snake apparently won’t slither away into the bushes because it seems to be waiting for an attack from his captors, Kadam tells me. We don’t know this for sure, but the ease with which Kadam handles the snake instils this blind, and foolhardy faith in his statement. He talks to me about boundaries and how if he respects those, the snake won’t bite him. He walks in circles around the snake to demonstrate how it mimics his movement in perfect rhythm..</h1>

<h1 class="full">Then, Kadam crouches in front of the snake and appears to be having a conversation. While the pair remain interlocked in this trans-like moment with the snake, till eventually, it decides that it’s safe enough to slither away into the safety of a shrub.</h1>

<h1 class="full">I dreamt of snakes that night.</h1>

<h1 class="full">On the second day of my documentation process, I arrive at Kadam’s house and am met with his extended family, which consists of some domestic and other not-quite-domesticated animals residing at his home. In cages outside and inside the house are the animals they have rescued, who need some more ‘laad pyaar’ as his mom says before they can be let go. Some have been abandoned and have been adopted by the family. His dad is leaving to teach young kids about animal awareness. He takes some of the pocket-sized companions — a rabbit, a fluffy cat, some small colourful birds, loud ducks, and the iguana named Charizard with him.</h1>

<h1 class="full">I’m walking around to observe the ducks in his backyard when I step on the shedded skin of a rattlesnake and I immediately scurry back inside. There’s a lull in the rescue operations these days, where Kadam would usually receive 20 calls a day from the concrete jungle that is Mumbai, it seems to be dwindling.. A few months ago, when the construction of Atal Setu was still underway, he would get multiple calls for snakes due to the destruction of the animal ecosystem in the area. Some even required him to get on a speedboat and rescue snakes from construction ships that were anchored deep in the ocean.</h1>

<h1 class="full">A rescue call came in this morning, just five minutes away from where we were. We reached a small building where a group of women in their morning kaftans and keds had already gathered outside, curious about the commotion. A few female gardeners in printed scarves and green jackets joined in too, trying to see what kind of snake it was.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Kadam, focused as ever, asked where it was. They all pointed upward. The mood was more excited than scared. We ran up to the first floor, and just as we reached the landing, I caught a glimpse of its tail. That’s when it hit me — why the hell was I in front?</h1>

<h1 class="full">Kadam spotted it and picked it up in one smooth motion. Despite its reputation, the snake was beautiful. All my nervous energy vanished. I forgot it was even supposed to be scary. The residents on the floor peeked out, phones out, recording videos for their WhatsApp groups.</h1>

<h1 class="full">The snake was golden-yellow, wriggling gently in Kadam’s hands. He moved with it carefully, supporting its body. As we headed back downstairs, he paused to let everyone take photos and ask questions. He explained patiently: it wasn’t venomous, it wouldn’t bite, and it was only there looking for a sunny spot to bask in. It was mating season, he added, which is why the males were so bright in colour. This one had just shed, which gave it that shiny, almost iridescent look.</h1>

<h1 class="full">We put it in a bucket of water to cool off. It relaxed, then curled its tail around Kadam’s wrist. He showed me where its heart was — you could actually see the scales moving with its breath. I touched it gently with one finger. I think it felt my pulse too. It started to get a bit agitated, probably because it could sense my fear. Kadam slipped it into his bag to release it somewhere quieter later.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Back at the office, his mum had made us kheema pao. She’s part of MARA and has been rescuing animals with her husband for over 30 years. She told me she used to go on snake rescues even when she was pregnant with Kadam. There’s a superstition that if a pregnant woman looks a snake in the eyes, her child will be born blind. She made it her mission to bust that myth.</h1>

<h1 class="full">At the building’s security desk, I noticed a torn poster Kadam must’ve put up ages ago — a list of venomous and non-venomous snakes. The boys told me people in Chembur don’t kill snakes anymore. They’ve created so much awareness that now everyone knows who to call and how to handle it.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Later, at home, Kadam’s mum was reading the paper. He placed a dying snake in front of her — it wasn’t going to make it. A few minutes later, it stopped moving. He placed it gently in front of the Buddha statue.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Before we could catch a breath, another call came in — this time from HP Gas Colony. A snake was caught in the netting. The guards greeted Kadam with respect. One man asked us to follow him on his bike to the spot.</h1>

<h1 class="full">The smell hit us first. Kadam didn’t hesitate. Someone handed him scissors, and he started cutting the net. It was a rat snake, non-venomous and common in the area. Kadam let it coil around him as he worked, unbothered.</h1>

<h1 class="full">The snake calmed down as if it could sense his energy. Right next to it, another snake had died, trapped and rotting. The smell was awful. Birds circled overhead. It was a senseless death. Kadam cut the dead snake loose too.</h1>

<h1 class="full">A few men had gathered by then, chatting and giving their opinions. Kadam picked a pink flower and a bit of tulsi, dug a small grave, and buried the snake.</h1>

<h1 class="full">As we drove home, I felt a mix of anger, sadness, and helplessness. Kadam told me about another superstition — apparently, in the Konkan region, people believe that if a rat snake pokes you with its tail, you’ll change genders. I can confirm that’s not true. I touched the tail and still feel like myself.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Snakes are strange creatures — always slipping between myth and reality. In Mumbai, they hide in drains, gardens, schoolyards, construction sites — always close, always just out of view.</h1>

<h1 class="full">After spending a few days with Kadam, I’m no longer paralysed by the idea of a snake slithering past my feet. But I’m also not cured of the discomfort, the inherited ickiness that still gives me goosebumps. Maybe that’s okay. We don’t need to love snakes. But we do need to learn how to live with them. And in the world he’s building — where children grow up knowing the difference between fear and respect — maybe fewer snakes will die for simply being snakes.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Earlier that day, a snake had wrapped itself around my neck and face — I let it, to let it “read” me. Kadam stood nearby, holding its head, guiding me. He told me to breathe slowly and wrap my hand around its heart. And just like that, it relaxed. So did I.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Photography: Tia Chinai</h1>