<h1 class="left">dirty: What does true authorship look like for women in cinema—and do you think we’ve seen it in Bollywood yet?</h1>

<h1 class="centre">Priyanka Bose: True authorship is when a woman isn’t just brought in to tell a story, but when she’s empowered to tell her story—without dilution, without being over-explained, without being filtered through what’s “marketable.” It’s when she can shape not just the narrative, but the process: who she casts, how she frames a scene, the rhythm of the edit, the politics of silence or speech.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">We’ve seen glimpses of this in Bollywood. There are women who are trying to push boundaries, no doubt. But the system still expects them to play by certain rules. If you’re a female filmmaker, especially one trying to tell stories that deviate from the norm, you often get slotted as “serious,” “niche,” or “festival-friendly.” That label is so limiting. It’s as if there’s no room for women to make commercial work with depth—or for commercial work to include the truths women actually live.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">Right now, what we mostly have is borrowed space. Beautiful moments, yes. But still fighting for permanence.</h1>

<h1 class="left">dirty: The idea of the “female gaze” is everywhere, but in Indian cinema, who actually gets to define it?</h1>

<h1 class="centre">PB: That’s the question, isn’t it? We throw around terms like “female gaze” as if they’re inherently progressive, but we rarely stop to ask who is holding the camera, who is funding the story, and who is allowed to speak.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">In Indian cinema, the female gaze often still passes through a male-owned lens—economically, creatively, and structurally. Even when women are behind the camera, the pressure to conform to market norms or dominant narratives is immense.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">Too often, the “female gaze” becomes just a softer, slightly more emotionally intelligent version of the male gaze—still focused on palatability, still confined to what a woman is expected to feel or portray. It’s rare to see rage, messiness, desire, contradiction—the full spectrum of womanhood—represented without judgment.</h1>

<h1 class="left">dirty: You’ve worked across borders—what do you notice about the kind of characters you’re offered abroad versus in India?</h1>

<h1 class="centre">PB: Abroad, there’s often more curiosity about the character, and about me as an actor. There’s a willingness to engage with complexity, to let a character be many things at once without rushing to explain or justify her. That doesn’t mean the roles are perfect or free of stereotype—far from it—but there’s at least an attempt to build from the inside out, rather than just dressing the part.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">In India, the starting point is often very different. It’s more visual, more surface-led. There’s still this obsession with “type”—how you look, what you’re perceived to represent. Especially for someone like me, who doesn’t fit the mainstream mould, I often get called in for roles that are “bold,” “unconventional,” or “gritty”—as if that’s the only space my body and presence are allowed to occupy.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">The irony is, the emotional range I get to explore abroad is often much wider than what I’m offered at home. And that stings, because I know the audience here is ready for more.</h1>

<h1 class="left">dirty: Bollywood has a history of boxing female leads into archetypes—the muse, the martyr, the manic. Do you think we’re just seeing updated versions of the same roles?</h1>

<h1 class="centre">PB: Absolutely. The packaging might have evolved—maybe she’s wearing better clothes, maybe she has a job now—but the core stereotypes are still very much intact. The muse has become the quirky, mysterious girl with a tragic past. The martyr is now the self-sacrificing working woman who somehow holds it all together without ever truly asking for anything. And the manic? She’s rebranded as the “unapologetic” woman—but only within limits. Because God forbid she stays that way by the end of the film.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">Let women be contradictory, boring, outrageous, and ordinary. Let them exist without justification. That’s where the real shift will come from—not from surface-level tweaks, but from letting women’s stories be as expansive and unclean as everyone else’s.</h1>

<h1 class="left">dirty: What archetype do you feel you’ve been cast into most often, and how difficult has it been to resist or break out of it?</h1>

<h1 class="centre">PB: I’ve often been cast as the “strong woman”,—and I say that with quotation marks because it’s rarely about true strength. It’s usually code for someone who suffers beautifully, quietly, with just the right amount of resilience to make her pain palatable. There’s a nobility expected in that suffering, a certain grace. But it’s still a box. And the problem with boxes is that they start to define not just how others see you, but sometimes how you begin to see yourself.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">Resisting that has been both intentional and exhausting. I’ve said no to work that might have paid my rent because it felt like a repetition of the same emotional blueprint. I’ve been told I’m too intense, too opinionated, too “niche”—as if complexity is a liability. But I’ve also been lucky to work in spaces outside Bollywood where there’s more room to stretch, to be ugly, loud, flawed, free.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">Breaking out of an archetype doesn’t happen once. It’s a constant negotiation between your own instincts as an artist and the industry’s need to reduce you to something legible. But I’ve learned that discomfort is part of that process.</h1>

<h1 class="left">dirty: Do repeated roles shape how the industry sees you, not just as an actor, but as a persona?</h1>

<h1 class="centre">PB: Completely. The industry doesn’t just watch your performances—it studies your patterns. If you’ve done one kind of role well, it assumes that’s all you’re capable of. And then that narrow slice of your work starts to calcify into your identity in the eyes of casting directors, producers, and even audiences.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">And it’s so limiting. Because it doesn’t allow space for surprise, for contradiction, for reinvention. It doesn’t ask what else she can do. It asks how she can do that same thing again, but at a cheaper, faster, shinier price.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">That’s why I try to resist easy packaging. I’m not a brand. I’m a body of work in motion. But it takes effort—daily, deliberate effort—not to internalise the industry’s gaze, and to keep insisting on the right to evolve.</h1>

<h1 class="left">dirty: Streaming platforms were expected to democratise storytelling. Do you think they’ve shifted the power dynamic, or just replicated old hierarchies in new spaces?</h1>

<h1 class="centre">PB: Initially, streaming felt like a revolution. Suddenly, there was space for quieter stories, flawed characters, regional voices, and actors who weren’t boxed into the typical Bollywood aesthetic. It felt like a breath of fresh air—like maybe, finally, content would drive casting, not the other way around.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">But over time, you start to see the same old power structures creeping back in—just dressed differently. Algorithms have replaced box office numbers, but the pressure to “perform” is still there, just rebranded as engagement metrics and watch time.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">That said, the door has been cracked open. There are more creators, more actors, more technicians getting visibility now than before. But visibility isn’t the same as power. True democratisation means that the people telling the stories also get to own them, and that’s still a battle.</h1>

<h1 class="left">dirty: Why do you think Bollywood resists experimentation in form and narrative? Is it the industry or the audience that’s hesitant?</h1>

<h1 class="centre">PB: I honestly think it’s more the industry than the audience. The audience has shown, again and again, that it’s open to fresh ideas, as long as they’re told with authenticity. People are hungry for nuance, for stories that reflect the chaos and contradictions of real life. It’s the industry that often underestimates them, defaulting to formulas and legacy structures out of fear.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">The industry runs on a deeply ingrained fear of losing money, but that fear is unevenly distributed. It’s not experimentation that scares Bollywood—it’s who gets to experiment. So we keep recycling stories and structures that feel “safe,” while new voices are either pushed to the margins or forced to self-censor before they even begin.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">What we need is not just courage, but trust—trust in audiences, in creators, and in the idea that cinema can be more than just commerce. Until that trust becomes part of the system, true experimentation will remain the exception, not the rule.</h1>

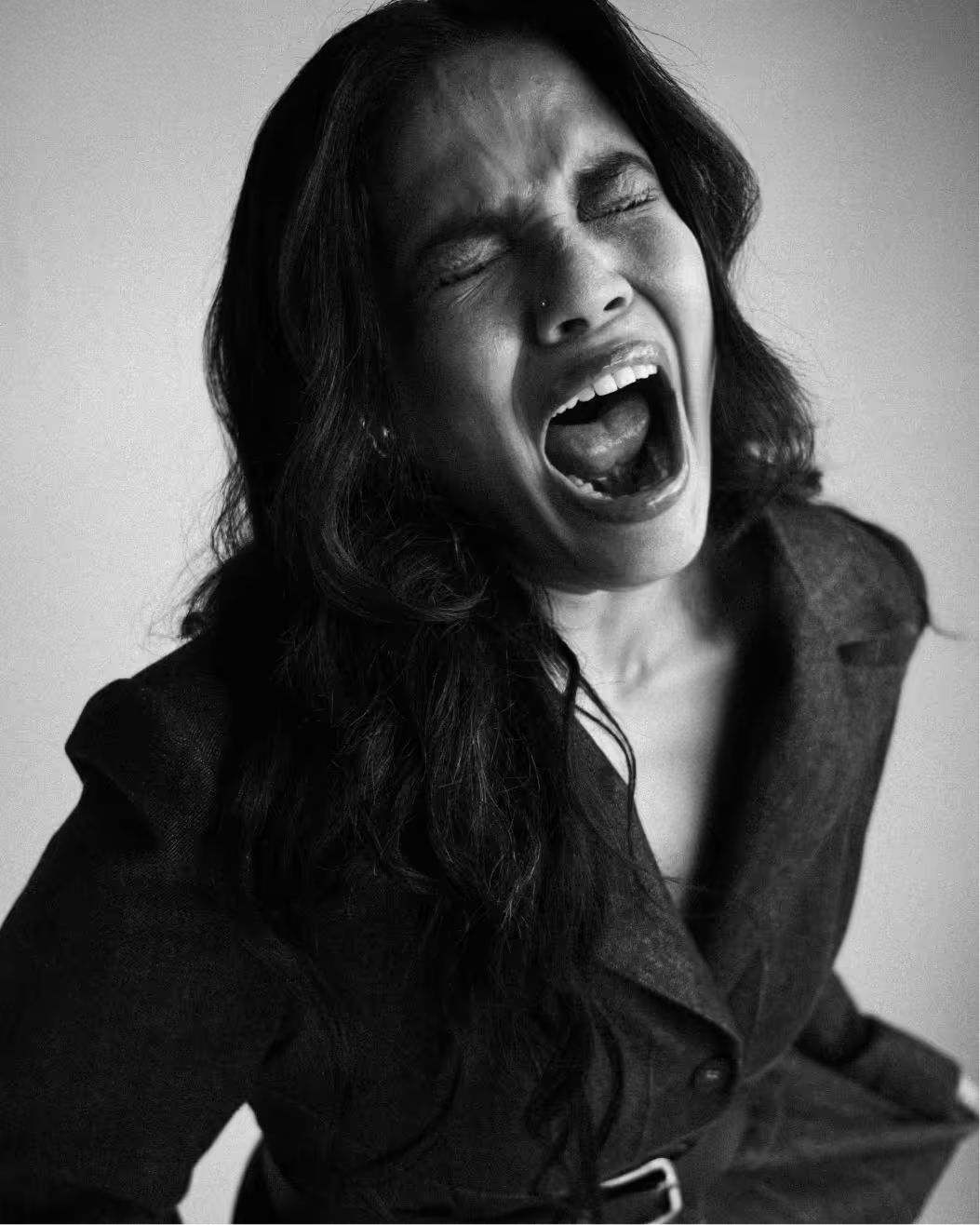

<h1 class="left">Photography: Mayank Sharma, Creative Direction/Styling: Gahan Choudhary, Hair and makeup: Shivani Joshi, Fashion Assistant: Prachi, Studio: Manoj Shah</h1>

<h1 class="left">Wardrobe: Urvashi Kaur, Econock, Moonray; Jewellery; Brands: Econock, Studio Metallurgy, Roma Narsingani; Footwear: Jeetinder Sandhu</h1>

<h1 class="full">dirty: What does true authorship look like for women in cinema—and do you think we’ve seen it in Bollywood yet?</h1>

<h1 class="full">Priyanka Bose: True authorship is when a woman isn’t just brought in to tell a story, but when she’s empowered to tell her story—without dilution, without being over-explained, without being filtered through what’s “marketable.” It’s when she can shape not just the narrative, but the process: who she casts, how she frames a scene, the rhythm of the edit, the politics of silence or speech.</h1>

<h1 class="full">We’ve seen glimpses of this in Bollywood. There are women who are trying to push boundaries, no doubt. But the system still expects them to play by certain rules. If you’re a female filmmaker, especially one trying to tell stories that deviate from the norm, you often get slotted as “serious,” “niche,” or “festival-friendly.” That label is so limiting. It’s as if there’s no room for women to make commercial work with depth—or for commercial work to include the truths women actually live.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Right now, what we mostly have is borrowed space. Beautiful moments, yes. But still fighting for permanence.</h1>

<h1 class="full">dirty: The idea of the “female gaze” is everywhere, but in Indian cinema, who actually gets to define it?</h1>

<h1 class="full">PB: That’s the question, isn’t it? We throw around terms like “female gaze” as if they’re inherently progressive, but we rarely stop to ask who is holding the camera, who is funding the story, and who is allowed to speak.</h1>

<h1 class="full">In Indian cinema, the female gaze often still passes through a male-owned lens—economically, creatively, and structurally. Even when women are behind the camera, the pressure to conform to market norms or dominant narratives is immense.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Too often, the “female gaze” becomes just a softer, slightly more emotionally intelligent version of the male gaze—still focused on palatability, still confined to what a woman is expected to feel or portray. It’s rare to see rage, messiness, desire, contradiction—the full spectrum of womanhood—represented without judgment.</h1>

<h1 class="full">dirty: You’ve worked across borders—what do you notice about the kind of characters you’re offered abroad versus in India?</h1>

<h1 class="full">PB: Abroad, there’s often more curiosity about the character, and about me as an actor. There’s a willingness to engage with complexity, to let a character be many things at once without rushing to explain or justify her. That doesn’t mean the roles are perfect or free of stereotype—far from it—but there’s at least an attempt to build from the inside out, rather than just dressing the part.</h1>

<h1 class="full">In India, the starting point is often very different. It’s more visual, more surface-led. There’s still this obsession with “type”—how you look, what you’re perceived to represent. Especially for someone like me, who doesn’t fit the mainstream mould, I often get called in for roles that are “bold,” “unconventional,” or “gritty”—as if that’s the only space my body and presence are allowed to occupy.</h1>

<h1 class="full">The irony is, the emotional range I get to explore abroad is often much wider than what I’m offered at home. And that stings, because I know the audience here is ready for more.</h1>

<h1 class="full">dirty: Bollywood has a history of boxing female leads into archetypes—the muse, the martyr, the manic. Do you think we’re just seeing updated versions of the same roles?</h1>

<h1 class="full">PB: Absolutely. The packaging might have evolved—maybe she’s wearing better clothes, maybe she has a job now—but the core stereotypes are still very much intact. The muse has become the quirky, mysterious girl with a tragic past. The martyr is now the self-sacrificing working woman who somehow holds it all together without ever truly asking for anything. And the manic? She’s rebranded as the “unapologetic” woman—but only within limits. Because God forbid she stays that way by the end of the film.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Let women be contradictory, boring, outrageous, and ordinary. Let them exist without justification. That’s where the real shift will come from—not from surface-level tweaks, but from letting women’s stories be as expansive and unclean as everyone else’s.</h1>

<h1 class="full">dirty: What archetype do you feel you’ve been cast into most often, and how difficult has it been to resist or break out of it?</h1>

<h1 class="full">PB: I’ve often been cast as the “strong woman”,—and I say that with quotation marks because it’s rarely about true strength. It’s usually code for someone who suffers beautifully, quietly, with just the right amount of resilience to make her pain palatable. There’s a nobility expected in that suffering, a certain grace. But it’s still a box. And the problem with boxes is that they start to define not just how others see you, but sometimes how you begin to see yourself.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Resisting that has been both intentional and exhausting. I’ve said no to work that might have paid my rent because it felt like a repetition of the same emotional blueprint. I’ve been told I’m too intense, too opinionated, too “niche”—as if complexity is a liability. But I’ve also been lucky to work in spaces outside Bollywood where there’s more room to stretch, to be ugly, loud, flawed, free.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Breaking out of an archetype doesn’t happen once. It’s a constant negotiation between your own instincts as an artist and the industry’s need to reduce you to something legible. But I’ve learned that discomfort is part of that process.</h1>

<h1 class="full">dirty: Do repeated roles shape how the industry sees you, not just as an actor, but as a persona?</h1>

<h1 class="full">PB: Completely. The industry doesn’t just watch your performances—it studies your patterns. If you’ve done one kind of role well, it assumes that’s all you’re capable of. And then that narrow slice of your work starts to calcify into your identity in the eyes of casting directors, producers, and even audiences.</h1>

<h1 class="full">And it’s so limiting. Because it doesn’t allow space for surprise, for contradiction, for reinvention. It doesn’t ask what else she can do. It asks how she can do that same thing again, but at a cheaper, faster, shinier price.</h1>

<h1 class="full">That’s why I try to resist easy packaging. I’m not a brand. I’m a body of work in motion. But it takes effort—daily, deliberate effort—not to internalise the industry’s gaze, and to keep insisting on the right to evolve.</h1>

<h1 class="full">dirty: Streaming platforms were expected to democratise storytelling. Do you think they’ve shifted the power dynamic, or just replicated old hierarchies in new spaces?</h1>

<h1 class="full">PB: Initially, streaming felt like a revolution. Suddenly, there was space for quieter stories, flawed characters, regional voices, and actors who weren’t boxed into the typical Bollywood aesthetic. It felt like a breath of fresh air—like maybe, finally, content would drive casting, not the other way around.</h1>

<h1 class="full">But over time, you start to see the same old power structures creeping back in—just dressed differently. Algorithms have replaced box office numbers, but the pressure to “perform” is still there, just rebranded as engagement metrics and watch time.</h1>

<h1 class="full">That said, the door has been cracked open. There are more creators, more actors, more technicians getting visibility now than before. But visibility isn’t the same as power. True democratisation means that the people telling the stories also get to own them, and that’s still a battle.</h1>

<h1 class="full">dirty: Why do you think Bollywood resists experimentation in form and narrative? Is it the industry or the audience that’s hesitant?</h1>

<h1 class="full">PB: I honestly think it’s more the industry than the audience. The audience has shown, again and again, that it’s open to fresh ideas, as long as they’re told with authenticity. People are hungry for nuance, for stories that reflect the chaos and contradictions of real life. It’s the industry that often underestimates them, defaulting to formulas and legacy structures out of fear.</h1>

<h1 class="full">The industry runs on a deeply ingrained fear of losing money, but that fear is unevenly distributed. It’s not experimentation that scares Bollywood—it’s who gets to experiment. So we keep recycling stories and structures that feel “safe,” while new voices are either pushed to the margins or forced to self-censor before they even begin.</h1>

<h1 class="full">What we need is not just courage, but trust—trust in audiences, in creators, and in the idea that cinema can be more than just commerce. Until that trust becomes part of the system, true experimentation will remain the exception, not the rule.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Photography: Mayank Sharma, Creative Direction/Styling: Gahan Choudhary, Hair and makeup: Shivani Joshi, Fashion Assistant: Prachi, Studio: Manoj Shah</h1>

<h1 class="full">Wardrobe: Urvashi Kaur, Econock, Moonray; Jewellery; Brands: Econock, Studio Metallurgy, Roma Narsingani; Footwear: Jeetinder Sandhu</h1>