<h1 class="left">Past the Sunday crowds, across the boating lake and Lion Safari Park Office, beyond a bridge over a brook and the Natural History Museum, a greying building houses the Wildlife Taxidermy Centre at Bombay's Sanjay Gandhi National Park. Around these parts, Dr. Santosh Gaikwad, India's only (official) taxidermist asserts his glorious reign with a steel fist of surgical tools. As we drive past the park's checkpoints, he rolls down the windows to tip his head ever so slightly, flashes a half-smile and raises a hand in nonchalant acknowledgment of the authorities. They recognise him instantly, stopping the car now and then to have a chat with the doctor, and he revels in the air of importance that comes with an editorial team present to photograph and interview him. The attention is warranted. There are few people in the country who can do what he does, legally at least. On arriving at our destination, he throws open the wooden doors of the taxidermy centre in a secluded spot of the park and welcomes us to the realm where he plays sovereign.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">Inside, we are greeted by his beloved subjects one after another, who act in obedience to the destinies and ways of life he has assigned to them. There's a peacock perched on wooden bark in the centre of the room, with a beady gaze that follows you wherever you go. The head of an elephant, hair and folds and tusk and all, is mounted on the side of the wall. A leopard, open-mouthed, mid-roar, stretches across the surface of a parapet, and Gaikwad rests an arm gingerly around his disfigured feline. There are paper-mache bodies, half-complete, of tigers and deer seated beside piles of cardboard boxes. There's a tool shelf with knives in the shape of every treacherous imagination. Acids are poured into plastic drinking water bottles of the past and labelled by hand. The walls are chipped and damp. The floor gathers fur and feathers. The smell of wet animal hide and chemical concoctions hangs in the air. Here, under tubelight skies and cement fort walls, charged by a burning passion of his own and some god-given divine right, Gaikwad becomes a creator of life after death.</h1>

<h1 class="left">It was in the year 2003 that Gaikwad first became interested in the art of taxidermy. He explains that he visited the Prince of Wales Museum in Bombay, now renamed the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, and was incredibly taken by the realistic representation of the animals on display in the museum's Natural History section. Working as Assistant Professor of Anatomy at the Mumbai Veterinary College then, he was in awe of how the animals' anatomy was preserved in death. He learned that the process referred to colloquially as 'stuffing' was really called taxidermy, a dying skill that had no teachers to set precedents, or courses covering its contents in this country. "But when your subconscious mind accepts an idea, it moves heaven and earth to bring it to pass," he says in all earnestness. It's an earnestness that caused the thought to take root so firmly in Gaikwad's head that he taught himself how to taxidermy. "Taxidermy combines the work of five professions cobbler art, sculpture, carpentry, painting and anatomy. Anatomy was already dear to me, so it was just a question of acquiring knowledge from people of the other four fields." And he certainly did.</h1>

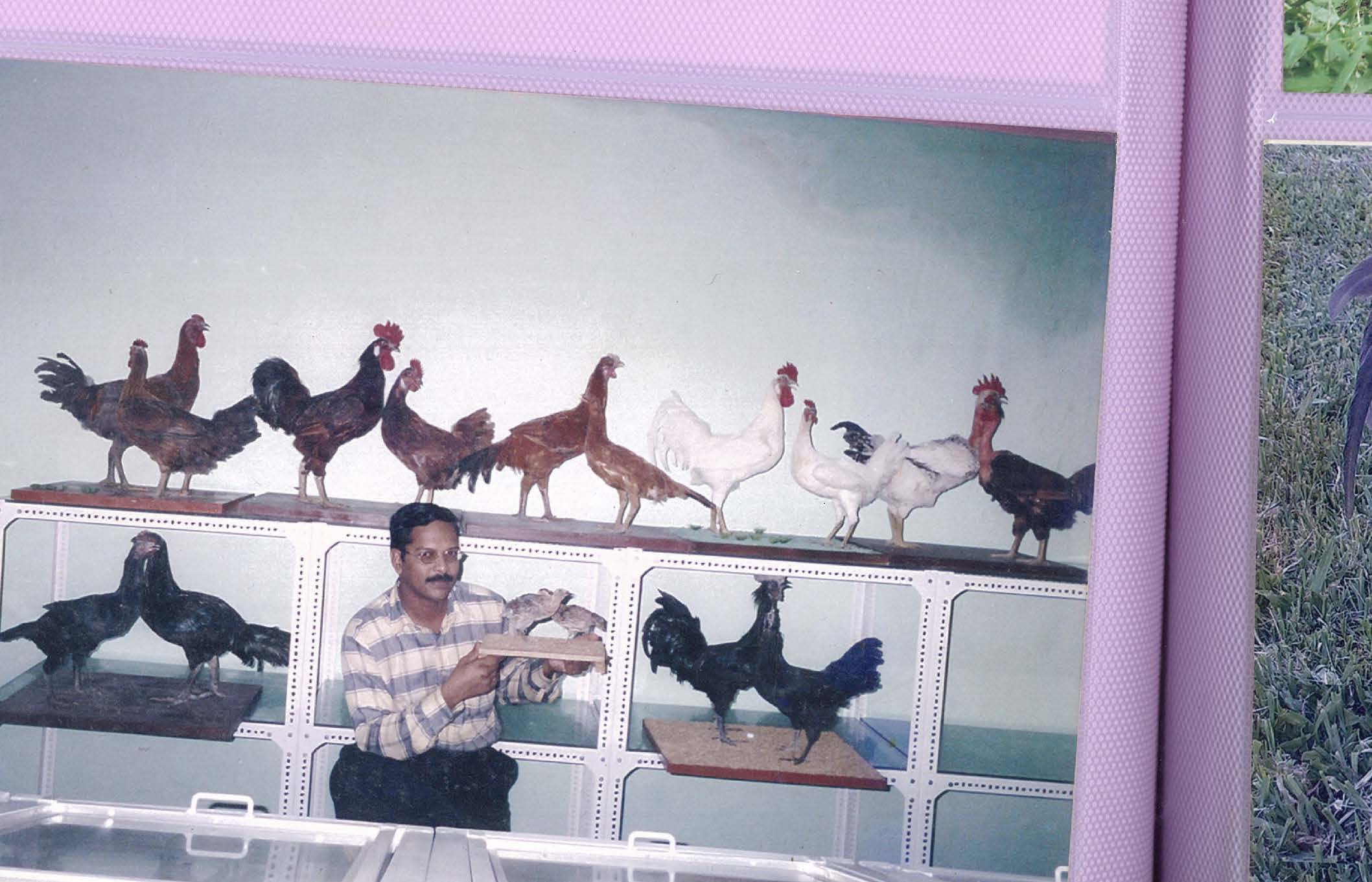

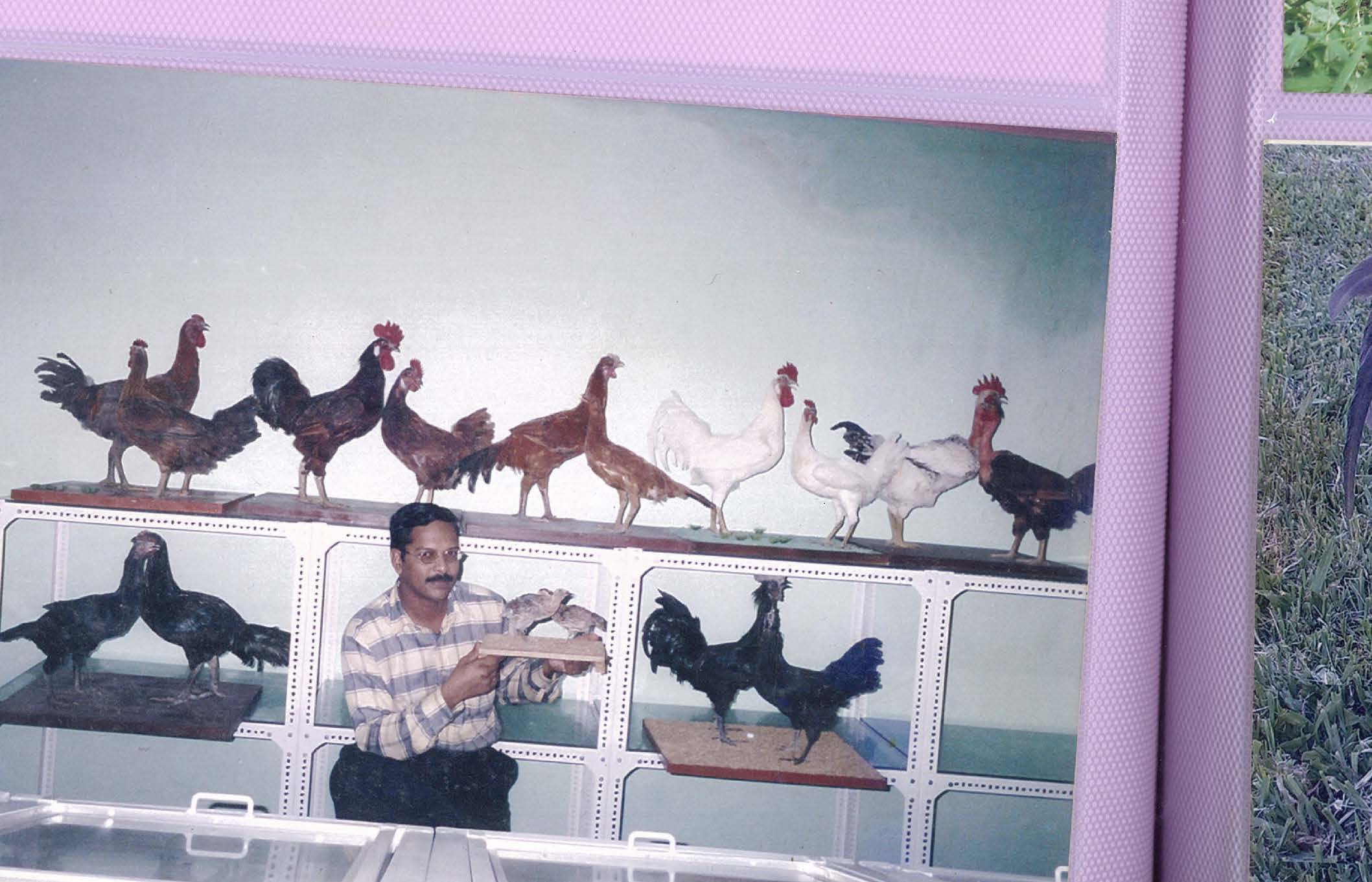

<h1 class="left">From his practice as a veterinary doctor, Gaikwad had access to dead birds in the hospital, whose bodies he'd bring home and store in the deep freezer to practise his art. Upon graduating from birds of all kinds, he'd skin, stuff and display fish until he was finally ready to work on mammals. Before he knew it, Gaikwad was performing taxidermy on small animals, dogs and cats, and being summoned by forest departments around the country to lend his expertise in the preservation of animals who died in nearby forest territories. He is especially grateful to the three former IFS (Indian Forest Service) officers from the state of Maharashtra who set up the first and only taxidermy centre in Sanjay Gandhi National Park along with the Mumbai Veterinary College, the latter being the institution where he works full-time. "This act of preservation of our 'rashtriya mrut van sampada' or dead national wildlife resource for research and education is supported by CZA (Central Zoo Authority, New Delhi) with a provision made for it in the Wildlife Protection Act 1972 as well. I feel happy that I can keep these resources alive for the next 80 to 100 years after their natural life. It is the optimum utilisation of a dead body that would otherwise have been spoiled."</h1>

<h1 class="left">He looks around the room and gestures vaguely at the work-in-progress bodies that dot his empire, those that he stopped short of resurrecting, owing to events as prosaic as a busy schedule an owl with sunken holes for eyes and big cats with wires for tails stare back. "Because of my full-time job at the Mumbai Veterinary College as a professor, I don't have as many hours in a day to finish my projects. I do my taxidermy practice whenever I have some free time on my hands." He admits that the entire process for a big cat should take a month or so, but for him, it could take anywhere up to a year. There are no other employees to be seen in the office space, Gaikwad runs the game by himself. "I'm doing it all alone, you know. I do have additional help sometimes but all the crucial work, I do with my own two hands. The skinning, tanning, stuffing and painting is a full-fledged operation that takes an awful lot of time. Taxidermists abroad have a lot more time and resources to perfect their art."</h1>

<h1 class="centre">By now he's swapped the silky blue shirt he came in wearing for old, work-appropriate clothes splattered surgical scrubs, flip-flops and no gloves. He has laid out his cluttering toolbox for a very visceral, visual demonstration of how he places skinned animals on a fleshing beam and scrapes flesh and fat off with a rampi (cobbler's knife), all spoken as if he were delivering news of what's on the breakfast menu. From an obscure corner, beside a rudimentary PVC tank containing [what I could only assume are] chemicals used for the tanning procedure, he picks up ageing, ochre skin that has already been subjected to treatment, with bare hands. "It's the skin of a lioness that I left halfway because I haven't had the chance to complete the taxidermy," he grins.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">It is also brought to our notice that the female elephant whose head we chanced upon on our tour earlier was called Vimla. She died in 2008, deep in the forest of Gadchiroli, a rural area of Maharashtra with a presence of Naxalite insurgents. When Gaikwad was called to the area to taxidermy the elephant from the neck up, the rest of her body having been cremated, many people told him not to go. "Everyone said it is a dangerous area, because of the Naxalites, and that I was foolish to even think of going. However, I was set in my belief that I was being called there for a purpose, to preserve the beauty of nature. I'm no uniformed policeman or politician; I was certain the Naxal groups would stay away and do me no harm." In the time he spent in the forest, he learned that the helpers who aided him in the taxidermy process hosted the insurgents in their houses for dal and rice at dinnertime. He stopped a mochi (carpenter) from getting on the last bus that leaves from the forest the man had earlier refused to help skin the animal, overwhelmed by the amount of fat, but eased up and got ready to work when supplied with liquid brown intoxicants. He braved mosquitoes, infections and other tribulations to bring Vimla's skin and skull back to Bombay, where he assembled her into life and gave her large, gentle eyes.</h1>

<h1 class="right">Wild animals aside, I'm curious to know how pet owners reach out to him for the process and what their reactions are like on seeing their taxidermied pet. "People usually find me through media, YouTube and the like, or letters from the Forest Department. They are always very sentimental because it's like they've lost a family member. They'll show me photographs of poses their beloved pet used to sit in and ask me if I can recreate the taxidermy in that exact manner. I've found that people prefer sitting poses for their pets, it's the more relaxed way." He goes on to narrate the story of a woman from Goa who dug up her dog from its grave 15 hours after its death, once she discovered that taxidermy exists and had found the person who could perform it for her pet. "I said no to that, of course, but I understand how emotional people can get after the death of someone they loved so much. Burning and burying destroys memories completely, so they want their pet to remain with them for as long as possible. I've seen tears roll down people's eyes while some others are absolutely overjoyed when they see the final result."</h1>

<h1 class="left">When Gaikwad talks of death and the emotions embroiled in losing a loved one, the science of his work is temporarily overtaken by the art of it all. The manner in which a paw is placed or a mouth is upturned is telling of the demeanour of the animal, he knows. His 20 years of practice may have made memory murky, but his heart softens and swells with pride when speaking of the animals he's worked with and his contributions to the field. "There is a soul inside the body called the cosmic life force, which controls all actions. When death occurs, there is a disconnection between body and soul, and what remains is called the dead body, or in scientific language, a cadaver. This cadaver can be used for organ donation, preservation, or taxidermy which can be extended to research and education. If a student can look at a taxidermied tiger in a museum, created exactly to mirror reality, and feel inspired and happy, my work is done."</h1>

<h1 class="centre">Standing surrounded by life of his own making, Dr. Santosh Gaikwad, tools and all, becomes an adversary to the imposing authority of death. He takes one long look at his creations and tells me, half-laughing but ever earnest, "inn sab ka antim sanskar mein hi karta hu."</h1>

<h1 class="centre">I'm the one who performs the last rites for each of these beings.</h1>

<h1 class="left">Photographer: Jedd Cooney</h1>

<h1 class="full">Past the Sunday crowds, across the boating lake and Lion Safari Park Office, beyond a bridge over a brook and the Natural History Museum, a greying building houses the Wildlife Taxidermy Centre at Bombay's Sanjay Gandhi National Park. Around these parts, Dr. Santosh Gaikwad, India's only (official) taxidermist asserts his glorious reign with a steel fist of surgical tools. As we drive past the park's checkpoints, he rolls down the windows to tip his head ever so slightly, flashes a half-smile and raises a hand in nonchalant acknowledgment of the authorities. They recognise him instantly, stopping the car now and then to have a chat with the doctor, and he revels in the air of importance that comes with an editorial team present to photograph and interview him. The attention is warranted. There are few people in the country who can do what he does, legally at least. On arriving at our destination, he throws open the wooden doors of the taxidermy centre in a secluded spot of the park and welcomes us to the realm where he plays sovereign.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Inside, we are greeted by his beloved subjects one after another, who act in obedience to the destinies and ways of life he has assigned to them. There's a peacock perched on wooden bark in the centre of the room, with a beady gaze that follows you wherever you go. The head of an elephant, hair and folds and tusk and all, is mounted on the side of the wall. A leopard, open-mouthed, mid-roar, stretches across the surface of a parapet, and Gaikwad rests an arm gingerly around his disfigured feline. There are paper-mache bodies, half-complete, of tigers and deer seated beside piles of cardboard boxes. There's a tool shelf with knives in the shape of every treacherous imagination. Acids are poured into plastic drinking water bottles of the past and labelled by hand. The walls are chipped and damp. The floor gathers fur and feathers. The smell of wet animal hide and chemical concoctions hangs in the air. Here, under tubelight skies and cement fort walls, charged by a burning passion of his own and some god-given divine right, Gaikwad becomes a creator of life after death.</h1>

<h1 class="full">It was in the year 2003 that Gaikwad first became interested in the art of taxidermy. He explains that he visited the Prince of Wales Museum in Bombay, now renamed the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, and was incredibly taken by the realistic representation of the animals on display in the museum's Natural History section. Working as Assistant Professor of Anatomy at the Mumbai Veterinary College then, he was in awe of how the animals' anatomy was preserved in death. He learned that the process referred to colloquially as 'stuffing' was really called taxidermy, a dying skill that had no teachers to set precedents, or courses covering its contents in this country. "But when your subconscious mind accepts an idea, it moves heaven and earth to bring it to pass," he says in all earnestness. It's an earnestness that caused the thought to take root so firmly in Gaikwad's head that he taught himself how to taxidermy. "Taxidermy combines the work of five professions cobbler art, sculpture, carpentry, painting and anatomy. Anatomy was already dear to me, so it was just a question of acquiring knowledge from people of the other four fields." And he certainly did.</h1>

<h1 class="full">From his practice as a veterinary doctor, Gaikwad had access to dead birds in the hospital, whose bodies he'd bring home and store in the deep freezer to practise his art. Upon graduating from birds of all kinds, he'd skin, stuff and display fish until he was finally ready to work on mammals. Before he knew it, Gaikwad was performing taxidermy on small animals, dogs and cats, and being summoned by forest departments around the country to lend his expertise in the preservation of animals who died in nearby forest territories. He is especially grateful to the three former IFS (Indian Forest Service) officers from the state of Maharashtra who set up the first and only taxidermy centre in Sanjay Gandhi National Park along with the Mumbai Veterinary College, the latter being the institution where he works full-time. "This act of preservation of our 'rashtriya mrut van sampada' or dead national wildlife resource for research and education is supported by CZA (Central Zoo Authority, New Delhi) with a provision made for it in the Wildlife Protection Act 1972 as well. I feel happy that I can keep these resources alive for the next 80 to 100 years after their natural life. It is the optimum utilisation of a dead body that would otherwise have been spoiled."</h1>

<h1 class="full">He looks around the room and gestures vaguely at the work-in-progress bodies that dot his empire, those that he stopped short of resurrecting, owing to events as prosaic as a busy schedule an owl with sunken holes for eyes and big cats with wires for tails stare back. "Because of my full-time job at the Mumbai Veterinary College as a professor, I don't have as many hours in a day to finish my projects. I do my taxidermy practice whenever I have some free time on my hands." He admits that the entire process for a big cat should take a month or so, but for him, it could take anywhere up to a year. There are no other employees to be seen in the office space, Gaikwad runs the game by himself. "I'm doing it all alone, you know. I do have additional help sometimes but all the crucial work, I do with my own two hands. The skinning, tanning, stuffing and painting is a full-fledged operation that takes an awful lot of time. Taxidermists abroad have a lot more time and resources to perfect their art."</h1>

<h1 class="full">By now he's swapped the silky blue shirt he came in wearing for old, work-appropriate clothes splattered surgical scrubs, flip-flops and no gloves. He has laid out his cluttering toolbox for a very visceral, visual demonstration of how he places skinned animals on a fleshing beam and scrapes flesh and fat off with a rampi (cobbler's knife), all spoken as if he were delivering news of what's on the breakfast menu. From an obscure corner, beside a rudimentary PVC tank containing [what I could only assume are] chemicals used for the tanning procedure, he picks up ageing, ochre skin that has already been subjected to treatment, with bare hands. "It's the skin of a lioness that I left halfway because I haven't had the chance to complete the taxidermy," he grins.</h1>

<h1 class="full">It is also brought to our notice that the female elephant whose head we chanced upon on our tour earlier was called Vimla. She died in 2008, deep in the forest of Gadchiroli, a rural area of Maharashtra with a presence of Naxalite insurgents. When Gaikwad was called to the area to taxidermy the elephant from the neck up, the rest of her body having been cremated, many people told him not to go. "Everyone said it is a dangerous area, because of the Naxalites, and that I was foolish to even think of going. However, I was set in my belief that I was being called there for a purpose, to preserve the beauty of nature. I'm no uniformed policeman or politician; I was certain the Naxal groups would stay away and do me no harm." In the time he spent in the forest, he learned that the helpers who aided him in the taxidermy process hosted the insurgents in their houses for dal and rice at dinnertime. He stopped a mochi (carpenter) from getting on the last bus that leaves from the forest the man had earlier refused to help skin the animal, overwhelmed by the amount of fat, but eased up and got ready to work when supplied with liquid brown intoxicants. He braved mosquitoes, infections and other tribulations to bring Vimla's skin and skull back to Bombay, where he assembled her into life and gave her large, gentle eyes.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Wild animals aside, I'm curious to know how pet owners reach out to him for the process and what their reactions are like on seeing their taxidermied pet. "People usually find me through media, YouTube and the like, or letters from the Forest Department. They are always very sentimental because it's like they've lost a family member. They'll show me photographs of poses their beloved pet used to sit in and ask me if I can recreate the taxidermy in that exact manner. I've found that people prefer sitting poses for their pets, it's the more relaxed way." He goes on to narrate the story of a woman from Goa who dug up her dog from its grave 15 hours after its death, once she discovered that taxidermy exists and had found the person who could perform it for her pet. "I said no to that, of course, but I understand how emotional people can get after the death of someone they loved so much. Burning and burying destroys memories completely, so they want their pet to remain with them for as long as possible. I've seen tears roll down people's eyes while some others are absolutely overjoyed when they see the final result."</h1>

<h1 class="full">When Gaikwad talks of death and the emotions embroiled in losing a loved one, the science of his work is temporarily overtaken by the art of it all. The manner in which a paw is placed or a mouth is upturned is telling of the demeanour of the animal, he knows. His 20 years of practice may have made memory murky, but his heart softens and swells with pride when speaking of the animals he's worked with and his contributions to the field. "There is a soul inside the body called the cosmic life force, which controls all actions. When death occurs, there is a disconnection between body and soul, and what remains is called the dead body, or in scientific language, a cadaver. This cadaver can be used for organ donation, preservation, or taxidermy which can be extended to research and education. If a student can look at a taxidermied tiger in a museum, created exactly to mirror reality, and feel inspired and happy, my work is done."</h1>

<h1 class="full">Standing surrounded by life of his own making, Dr. Santosh Gaikwad, tools and all, becomes an adversary to the imposing authority of death. He takes one long look at his creations and tells me, half-laughing but ever earnest, "inn sab ka antim sanskar mein hi karta hu."</h1>

<h1 class="full">I'm the one who performs the last rites for each of these beings.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Photographer: Jedd Cooney</h1>