<h1 class="left">When my friend, who teaches Politics at King's College London, tried to set me up with a finance guy studying at LSE, I never expected our first phone call to turn into a linguistic revelation. "It would be so romantic to have my partner read Urdu novels to me," he mused. His confidence caught me off guard. Here was a Dakhni Muslim man, effortlessly fluent in a dialect I had never fully encountered, yet unable to read the Lucknowi Urdu I had always considered my own. I had long believed I was proficient in Urdu—until he asked me to switch from English to Urdu. That simple request exposed a truth I had been ignoring: my grasp of the language had slipped. While my bond with my mother tongue has been tenuous, my relationship with love has never felt stronger. That LSE guy? He’s now my fiancé.</h1>

<h1 class="left">If there’s one thing I have come to understand, it’s that love finds you—but only when the timing and place are just right. For us, it wasn’t just romantic chemistry; it was a shared curiosity about languages, cultures, and traditions. Early in our courtship, we spoke about the languages we knew, struggled with, and hoped to learn together. I’d read to him from Asrar-e-Khudi, which he had only read in English, but longed to experience in Urdu. In return, he introduced me to Dakhni, teaching me idioms, couplets, and slang. He’s now in Bengaluru, managing his family business; I’m in Edinburgh, finishing a PhD. Some mornings, I wake with an image of us reading to each other. Even if life gives us little, we’ll have that—our shared love for reading. My mother laughs, but the idea only deepens my resolve to reclaim my hold on Urdu.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">As a language, Urdu flourished in India until the late 1980s, but has been steadily declining, and like many third-generation speakers, I had unknowingly distanced myself from my linguistic heritage. The dominance of English and Western cultural influences had eroded the everyday presence of Urdu in my life. While I thought I had Urdu in my bones—until these conversations with my fiancé, I suddenly felt the weight of what I had lost. Determined to reclaim it—and, if I'm being honest, to impress him—I called my father and asked if he would be my Urdu tutor. Thus began my journey of rediscovering my mother tongue.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">My father, now in his seventies, a retired regional auditor and a lawyer by academic training, was touched. “Urdu is just like that vine in our ancestral home”, he mused. “Still alive. But barely.” As I tried to polish my everyday Urdu, he mourned the language's grand decline—one he had witnessed firsthand. Once the language of tehzeeb (refinement) and akhlaq (ethics), Urdu was not just a language but a bridge across diverse communities. Ishtiaq H. Qureshi noted, "While Persian remained the official language of the Mughal court, Urdu became the language of everyday use for intercommunication among the different communities regardless of their creed…" (1977, p. 101), cementing its role as a primary language in South Asia.</h1>

<h1 class="right">While details can be murky, there is some evidence that Urdu held official status in British India alongside English. But in post-independence India, the language began to slip from public consciousness, even as it held official status in states like Uttar Pradesh. Today, its presence feels ghostly—familiar yet fading. In the increasingly polarised world we currently reside in, Urdu is not just losing its cultural significance but becoming increasingly obsolete. My father laments the time when Urdu was not exotic—it was everywhere. It adorned newspapers, advertisements, literary and cultural magazines, film posters, love letters, and shopfronts; a language of courtrooms, conversation, and community.</h1>

<h1 class="right">He particularly reminisces about when brand adverts in North India would appear in both Hindi and Urdu. He recalls full-page spreads in Urdu newspapers and magazines—ads that paired glamorous film stars like Madhubala, Rekha, or a young Amitabh Bachchan with elegantly calligraphed Urdu slogans. After looking through some of the archives myself, I found that brands like Lux, with their celebrity-studded campaigns, were often advertised as "filmi sitaaron ka husn bakhsh saabun", promising the secret to star-like beauty. The poetics of the language made an everyday product, as small as a soap, aspirational. He gets nostalgic about the old Bata campaigns. Still a teenager then, he would compare those shoes to today’s Loro Piana—as if owning a pair meant you had truly arrived.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">What stays with me, though—perhaps it’s the architect and designer in me—is the sheer beauty of those adverts. There’s something about the black-and-white aesthetic, the sleekness of hand-drawn flourishes, the floral typefaces. They had restraint, grace, and a kind of quiet confidence—very different from the overproduced visuals we see now. Everything looked intentional. Even when the product was as simple as a bar of soap, the ad carried a kind of elegance you don’t find in the hyper-saturated, over designed templates of today. For my father, however, it was never just about the product or the advert. It was about the language, the way Urdu once held a significant space in the public imagination.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Urdu:

حسین نرملا کا محافظ جلد لکس ٹوائلٹ صابن ہے

لکس ٹوائلٹ صابن

فلمی ستاروں کا حسن بخش صابن</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Roman Urdu:

Haseen Nirmala ka muhafiz jild hai Lux toilet sabun

Lux toilet sabun

Filmi sitaaron ka husn bakhsh saabun</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

English:

Lux toilet soap is the protector skin of beautiful Nirmala

Lux Toilet Soap

The beauty-bestowing soap of film stars</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Urdu:

"لَکس کو میں اب اور بھی پسند کرنے لگی ہوں...

"!کتنی دلفریب ہے اس کی نئی خوشبو

ہیما مالنی—

لکس — فلمی ستاروں کا خالص، نرم صابن</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Roman Urdu:

"Lux ko main ab aur bhi pasand karne lagi hoon...

kitni dilfareeb hai iski nayi khushboo."

— Hema Malini

Lux — filmee sitaaron ka khaalis, naram saabu</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

English:

"I’ve started liking Lux even more now...

its new fragrance is simply enchanting."

— Hema Malini

Lux — the pure, gentle soap of film stars</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Urdu:

ایمبیسیڈر

خوش وضع جوتے

ممتاز آدمیوں کے لیے

خوش وضع بَلو سرکٹ جوتے — کیچڑ سے

محفوظ رکھنے والا اگلا حصہ — آرام دہ

ملائم، کاف کا اَپر — سیاہ یا بادامی

رنگوں میں — چمڑے کا تَلا</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Roman Urdu:

Ambassador

Khush-wazaa jootay

Mumtaz aadmiyon ke liye

Khush-wazaa Blu Circuit jootay — kichad se

Mahfooz rakhne waala agla hissa — aaram deh

Mulaayam, kaaf ka upper — siyaah ya baadami

Rangon mein — chamray ka tala</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

English:

Ambassador

Elegantly designed shoes

for distinguished men.Elegantly designed Blu Circuit shoes — protected against mud

A front section built for safety — and comfort

Soft, with a 'Kaaf-style' upper — in black or tan

Available in shades — with a leather sole</h1>

<h1 class="left">Although some Urdu newspaper titles are still circulating, once-ubiquitous brands like Lux, Ponds and Pears, once regulars in Urdu newspapers, have stopped marketing in Urdu. That lyrical branding—once so common, so comforting—has quietly disappeared. Brands no longer advertise in Urdu not because it does not sell, but because it has become politically inconvenient. A 2021 FabIndia Diwali ad, which refers to the name of their Diwali collection, Jashn-e-Riwaaz, a phrase that means "celebration of tradition" in Urdu, faced backlash for being "culturally inappropriate"—a reminder of how weaponised language politics has become.</h1>

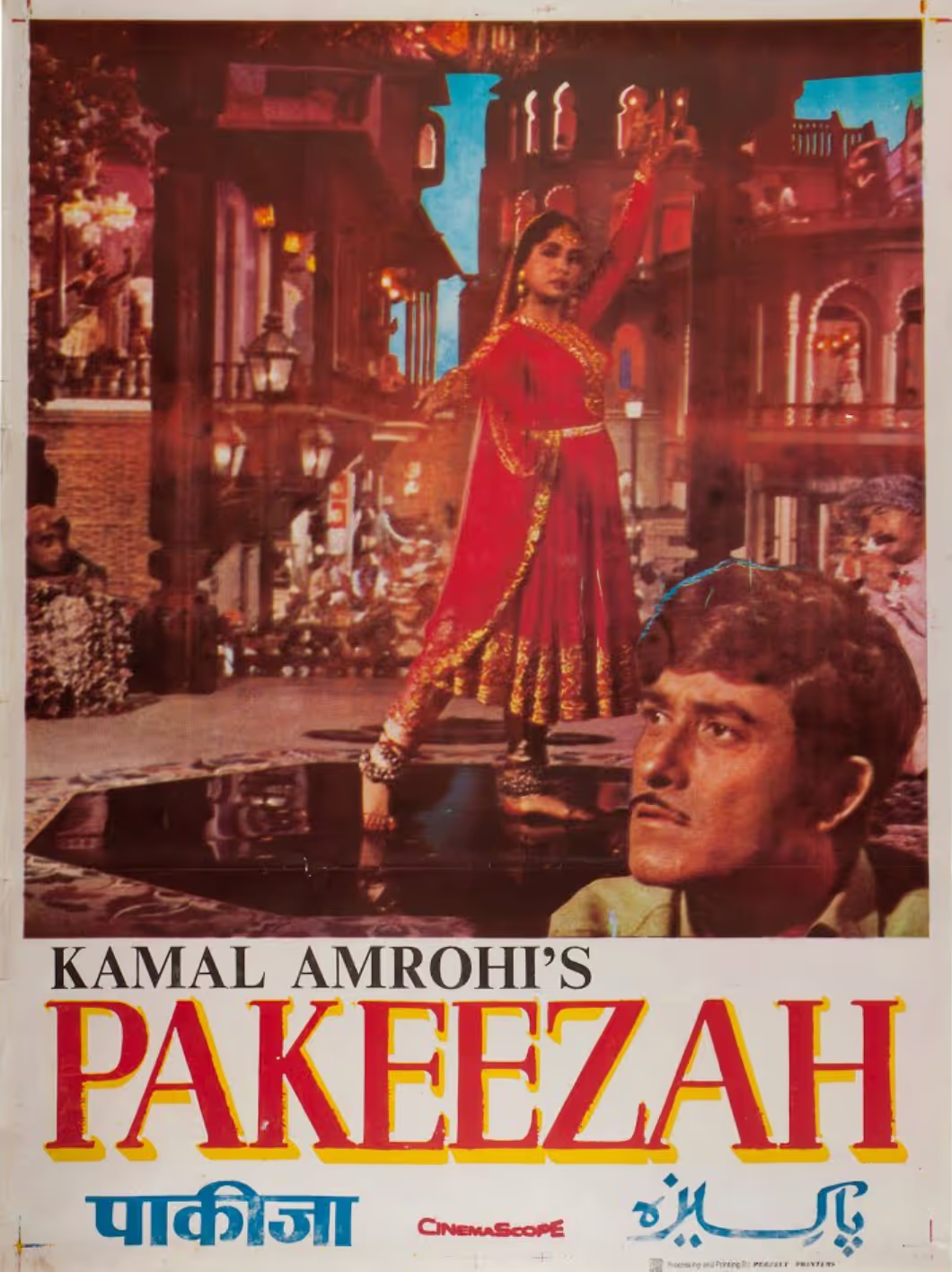

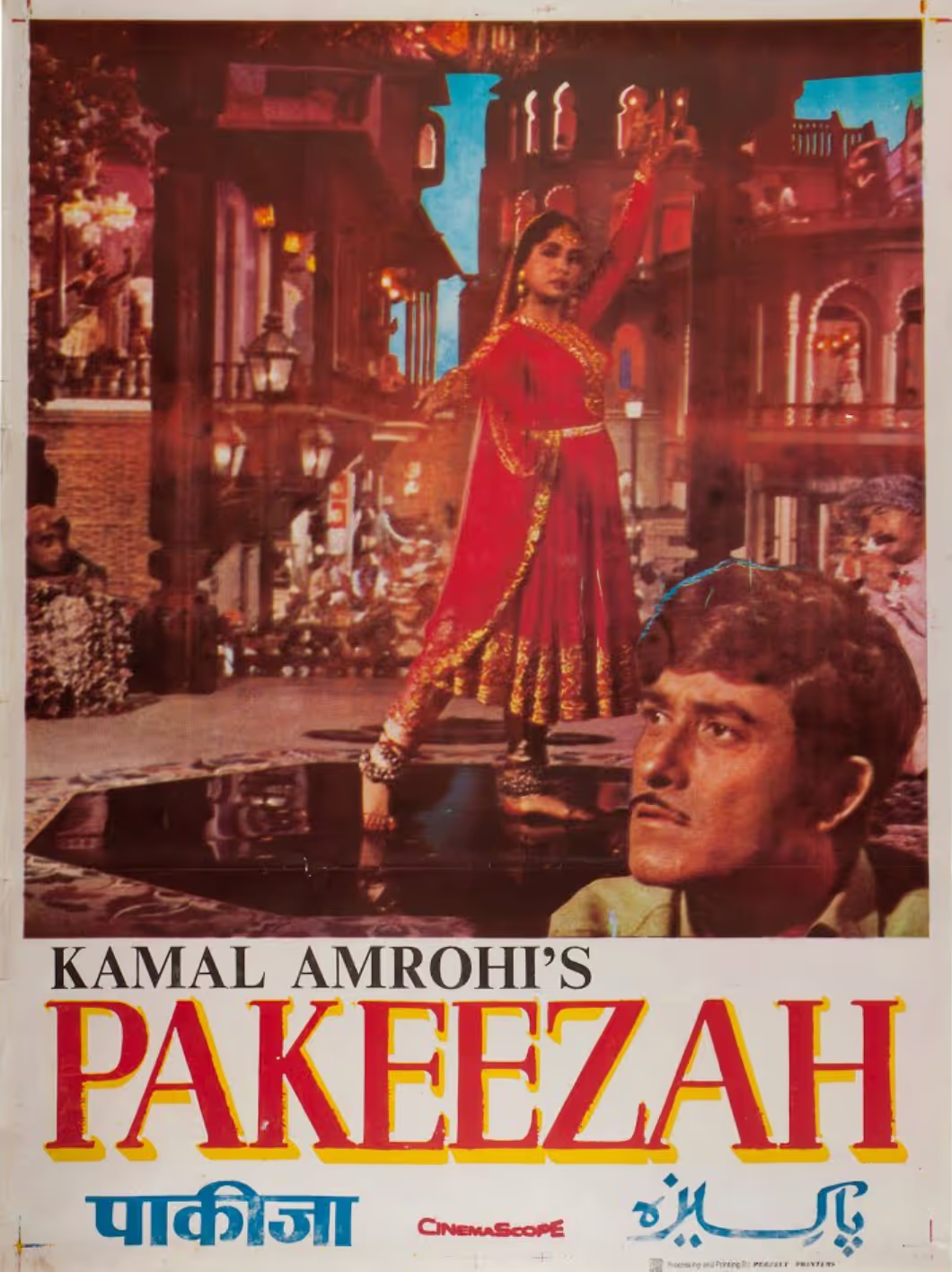

<h1 class="centre">Cinema, too, turned away. My father mentions that until the 1980s, Bollywood film posters were trilingual—Hindi, English, and Urdu—that spoke to India's plural identity. What intrigues me most about these film posters is their hand-painted aesthetic—bold, eclectic colours, ornate designs, and, of course, the linguistic inclusivity. But by 1989, Urdu had all but vanished. Take Ram Lakhan, released in January: the main title sequence still featured all three languages. Contrast it with Maine Pyar Kiya, released in December that year, which marked Urdu's erasure from mainstream cinema visuals. The reasons were many: rising tensions with the neighboring country, shrinking numbers of Urdu-speaking screenwriters, and changing audience demographics.</h1>

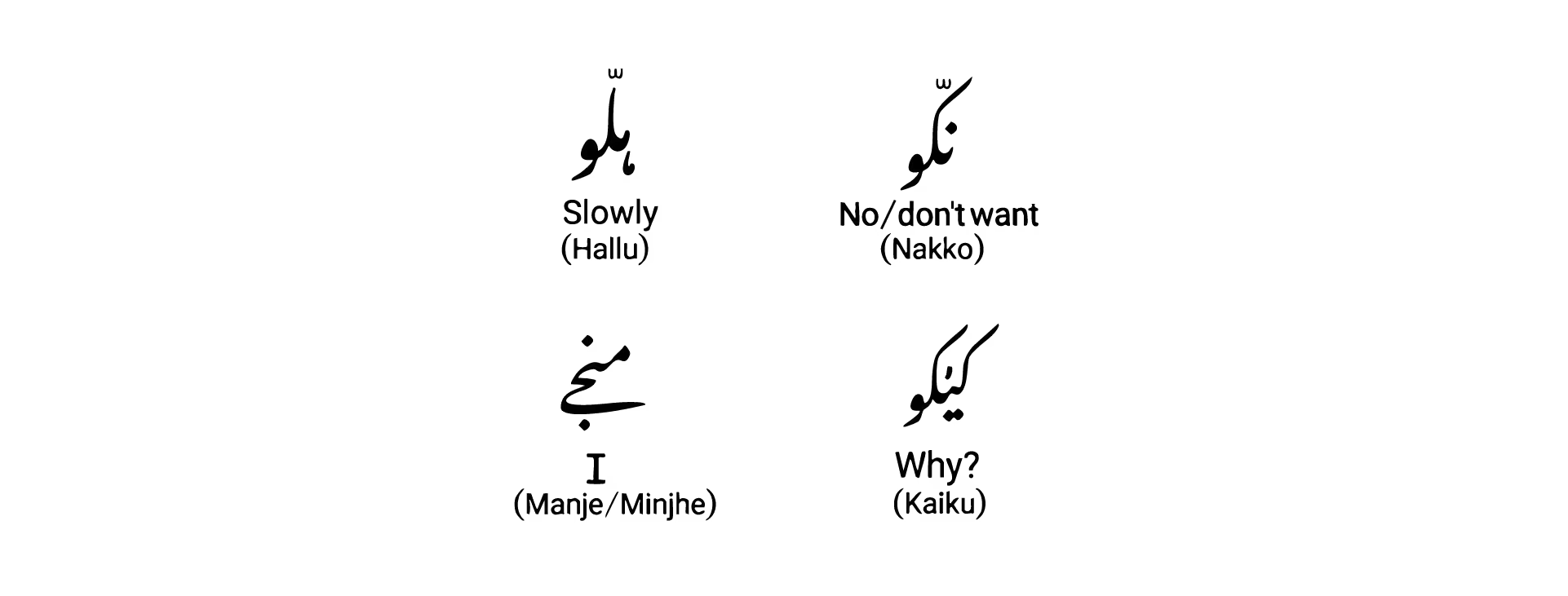

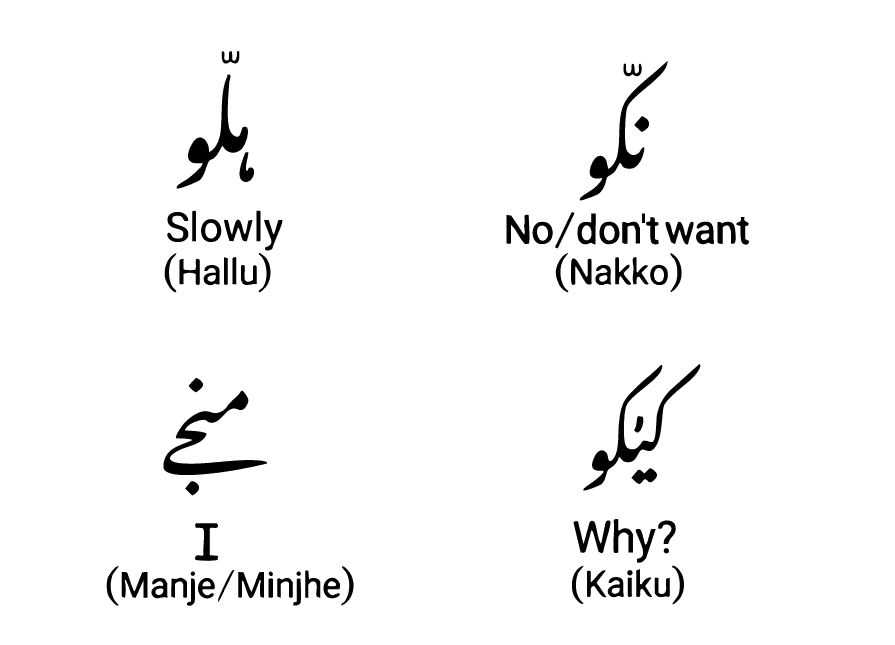

<h1 class="left">On the other hand Dakhni, which may have faded from literary prominence over the past 80 years due to a lack of official patronage, continues to thrive as a spoken dialect of Urdu across South India. The key distinction lies in usage: people converse in Dakhni, but write in standard Urdu. Its survival owes much to its local speakers as well as to Deccani films and stage dramas, which gained immense popularity in the early 2000s, and more recently, to social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok. Interestingly, Dakhni adapts itself to the local linguistic landscape: Chennai Dakhni blends with Tamil, Bangalore Dakhni aligns with Kannada, and Hyderabad Dakhni draws heavily from Telugu.</h1>

<h1 class="left">My fiancé has introduced me to a range of slapstick Deccani movies and dramas that became cultural phenomena in the South. Titles like The Angrez, Hyderabadi Nawabs I & II, Gullu Dada Returns, and Gangs of Hyderabad are films we've attempted to watch together over FaceTime as a way to understand the local flavour of Dakhni culture. Though the dialogue is entirely in Dakhni, the posters and marketing materials are often in English—a telling detail about their targeted appeal. The Angrez, in particular, and one of its characters, Saleem Pheku, found a significant following not just among local audiences but also within the South Indian diaspora in the Middle East, UK and the USA.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Dakhni Urdu (as spoken):

Poison boley toh scent ko boltey. Baahar milta.

– Saleem Pheku, The Angrez</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Standardised urdu script (with Dakhni style preserved):

پوئزن بولے تو سینٹ کو بولتے۔ باہر ملتا۔

– سلیم فیکو، دی انگریز</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

English Translation:

"Poison, as in, that's what we call scent. You get it abroad."

– Saleem Pheku, The Angrez</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Dakhni Urdu (as spoken):

Aisich kaam karey toh apan popular hotey</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Standardised urdu script (with Dakhni style preserved):

ایسچ کام کرے تو اپن پاپولر ہوتے

Note: "اپن" (apan) = "ہم" (hum) in standard Urdu, used casually in Dakhni to mean "we / I (humble)".</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

English Translation:

If we worked like this, we'd become popular.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

---</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Bengaloor ki Daastan by Pasha</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Dakhni Urdu (as spoken):</h1>

<h1 class="left">

Bengaloor ki daastan, suni toh hogi aapne

Maarte so faile aur baat karte baadme

Dil ke saaf khaali apni baat mech maghroor hame

Ek jigra, dusra daring, yeh do cheezan se mashoor hame</h1>

<h1 class="left">

Ghafoor hame, sabme bade lekin soch chotich

Seeda kya b dikta nai khaali dikhte note-ich

Ek pantar aaji baaji chaar-paanch showpiece

Ki kati iska bawa MLA uska bawa Police</h1>

<h1 class="left">

Hero khudke vaste, dusryan ku villain hume

Daaru peete nai, pilate pooryan ku chillum hame

Rupay kya cheez Dubai jaako kamalinge Dirham

Apne area mein sher, picche gully mein hiran hame</h1>

<h1 class="left">

Standard Urdu Script (with Dakhni style preserved):</h1>

<h1 class="left">

بنگلور کی داستان سنی تو ہوگی آپ نے

مارنے والے تو بہت ہیں، بات کرتے بعد میں

دل کے صاف، خالی، اپنی بات میں مغرور ہم

ایک جگر والا، دوسرا دلیر، یہی دو چیزیں ہمیں مشہور کرتی ہیں</h1>

<h1 class="left">

غفور ہم، سب میں بڑے لیکن سوچ چھوٹی

سیدھا کیا دکھتا ہے، خالی دکھتے ہیں نوٹ

ایک پتھر آج بازی، چار پانچ شو پیس

کہتے ہیں اس کا باوا ایم ایل اے، اس کا باوا پولیس</h1>

<h1 class="left">

ہیرو خود کے واسطے، دوسروں کو ولن ہم

شراب پیتے نہیں، پلانے والے پورے چِلّم ہم

روپے کیا چیز، دبئی جا کے کمائیں گے درہم

اپنے علاقے میں شیر، پیچھے گلی میں ہرن ہم</h1>

<h1 class="left">

English Translation:</h1>

<h1 class="left">

You must have heard the tale of Bangalore,

Many are quick to fight, but talk comes afterward.

With a pure and empty heart, proud of our own words,

One with courage, the other daring—these two traits make us famous.</h1>

<h1 class="left">

We are Ghafur, great among all but with small thoughts,

What appears straightforward is not; only the money is visible.

One stone today, four or five showpieces,

They say his father is the MLA, his father the police.</h1>

<h1 class="left">

We are heroes for ourselves, villains to others,

We don’t drink alcohol, but those who serve it smoke chillum fully.

What are rupees? We’ll earn Dirhams by going to Dubai,

In our area, we are lions; behind in the alley, we are deer.</h1>

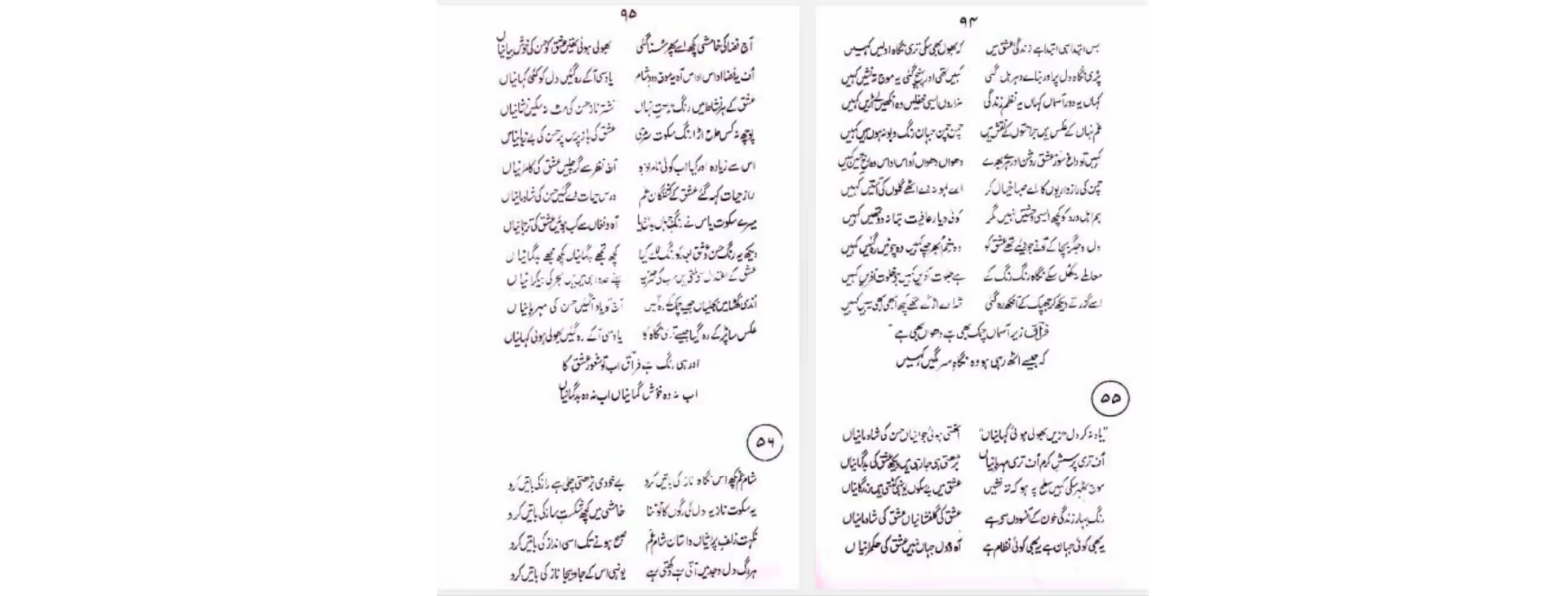

<h1 class="centre">In mainstream media, actor Mehmood Ali popularised Dakhni lingo in the early '90s, though much of the cinematic use of the dialect has been confined to comedy, contrary to the romanticised appeal of Urdu. However, in recent years, social media and the rise of Desi hip-hop have shifted the perception of Dakhni. Artists like Mohammad Affan Pasha, whose rap lyrics are rooted in everyday street Dakhni and far removed from parody, are helping reclaim the dialect as something more textured and authentic. Stand-up comedians still rely on its comic potential, but Dakhni is slowly beginning to express a broader cultural and emotional range. While its so-called dialect thrives in the streets, homes, music, and everyday life of the locals, my father mourns the gradual disappearance of Lakhnavi Urdu.</h1>

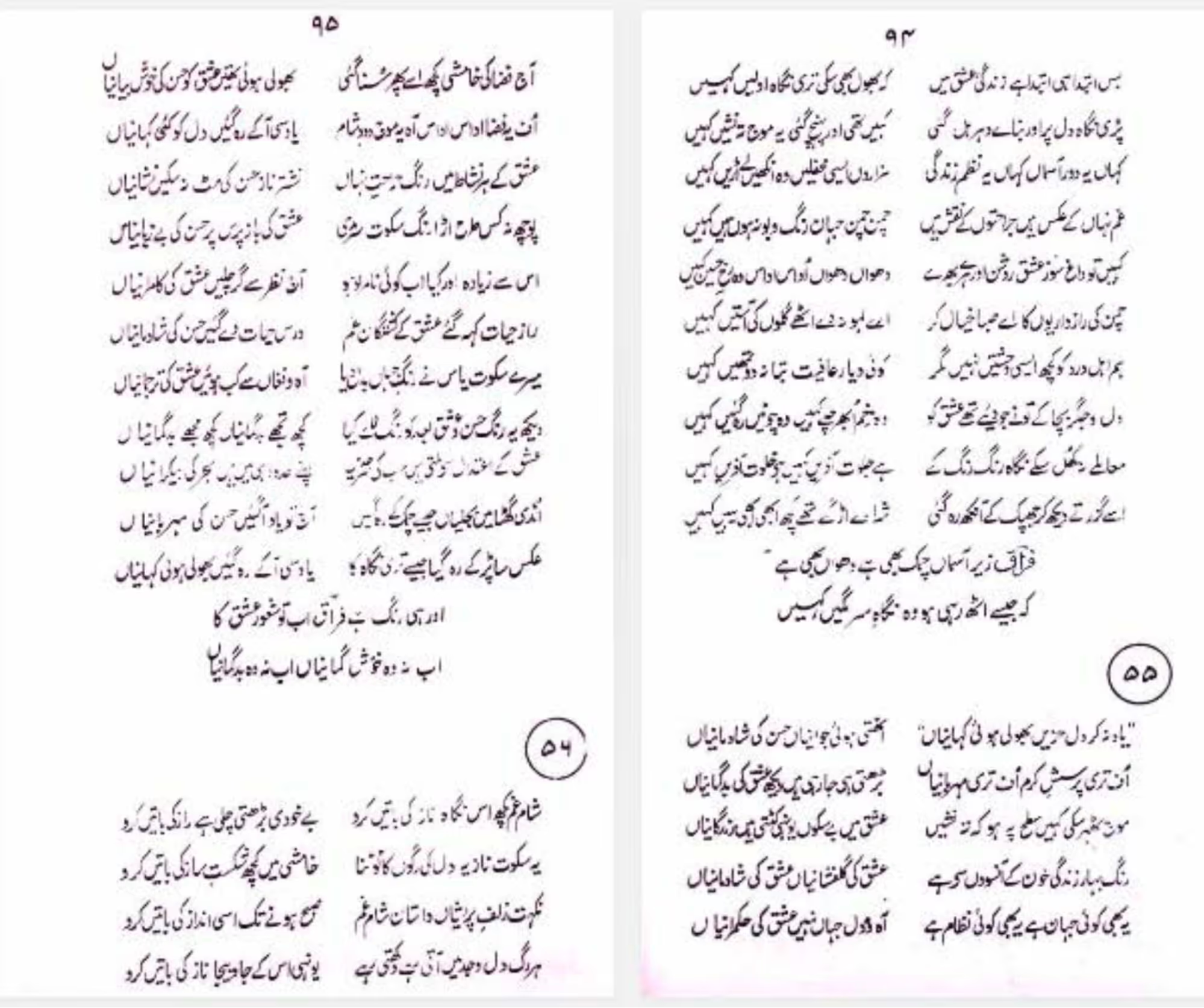

<h1 class="right">He particularly shares his quiet nostalgia for the days when he would write letters in Urdu—something he hardly gets to do anymore, thanks to the digital age. He remembers his letters to my mother from when they got stuck in their hometowns a few weeks after their wedding, due to the 1980s curfew in Western Uttar Pradesh. Delicate, handwritten, dipped in a sense of (be)longing and now replaced with FaceTime and WhatsApp. "There is no such firaaq (separation) anymore," my mother smirks. Romance, in its classic Urdu form, does not translate well on digital screens. My fiancé and I joke about it too—we are continents apart, yet never more than a tap away. And anyway, despite being fluent in Arabic, the Urdu script still feels alien to him. So writing Urdu letters to him will remain a dream.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Urdu:

شامِ غم کچھ اُس نگاہِ ناز کی باتیں کرو

بے خودی بڑھتی چلی ہے راز کی باتیں کرو</h1>

<h1 class="right">

یہ سکوتِ ناز، یہ دل کی رگوں کا ٹوٹنا

خاموشی میں کچھ شکستِ ساز کی باتیں کرو</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

نکہتِ زلفِ پریشاں، داستانِ شامِ غم

صبح ہونے تک اسی انداز کی باتیں کرو</h1>

<h1 class="right">

کچھ قفس کی تیلیوں سے چھن رہا ہے نور سا

کچھ فضا، کچھ حسرتِ پرواز کی باتیں کرو</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

جس کی فُرقت نے پلٹ دی عشق کی کایا فراق

آج اُسی عیشِ نفسِ دم ساز کی باتیں کرو</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Roman Urdu:

Shaam-e-gham kuchh us nigah-e-naaz ki baatein karo

Bekhudi barhti chali hai, raaz ki baatein karo</h1>

<h1 class="right">

Yeh sukoot-e-naaz, yeh dil ki ragon ka tootna

Khamoshi mein kuchh shikast-e-saaz ki baatein karo</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Nekhat-e-zulf-e-parīshāñ, dāstān-e-shaam-e-gham

Subh hone tak usī andāz kī bāteñ karo</h1>

<h1 class="right">

Kuchh qafas ki teeliyon se chhan raha hai noor sa

Kuchh fiza, kuchh hasrat-e-parwaaz ki baatein karo</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

Jis ki furqat ne palat di ishq ki kaaya Firaq

Aaj usi aish-e-nafas-e-dam-saaz ki baatein karo</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

English:

In this evening of sorrow, speak of that tender glance;

Ecstasy is rising—let's speak in the language of secrets.</h1>

<h1 class="right">

This graceful silence, this breaking of the heart’s veins—

In this quiet, speak of broken melodies.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

The fragrance of tangled hair, the tale of the sorrowful night—

Until morning comes, let such themes linger in our talk.</h1>

<h1 class="right">

Some light filters through the bars of the cage—

Speak of the air, speak of the yearning to fly.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">

The one whose absence transformed the very essence of love, O Firaq—

Today, speak of the joy in the breath that echoes their presence.</h1>

<h1 class="left">The Urdu he can't read—Lucknavi, polished, poetic—is the one he wants our children to learn. Dakhni, his mother tongue, he fears is too raw, too unrefined, but my fiancé is not alone in this anxiety. Bengaluru-based rapper Pasha, who performs in Dakhni, has spoken of his discomfort speaking Dakhni in public, often switching to Hindi out of the fear of being ridiculed. Today, he stands proudly in his linguistic identity, using music to reclaim space and dismantle the shame once tied to Dakhni. Similarly, heritage storyteller and journalist Yunus Lasania has long pushed back against the notion that Dakhni is somehow lesser than Urdu or that it is language only suited for parody.</h1>

<h1 class="left">The binary—Hindi as the language of the masses, Lucknavi Urdu as sophisticated, Dakhni as raw—reveals deeper cultural anxieties. Do we always have to choose between eloquence and intimacy? Between nazakat and apnapan? The internet loves to argue: Is Dakhni a dialect or a language in its own right? Lasania sees this divide as a product of linguistic hegemony, particularly from the North, where Dakhni is viewed as Urdu’s lesser sibling. I argue otherwise: Dakhni, with its casual tone and local flavour, is rich in emotion. It speaks of homes, but it also speaks of humans. It is not lesser; it is just different. As I navigate this duality—researching Dakhni while preserving my Lucknavi heritage—I’ve come to realize that both languages are on the verge of fading.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">Dakhni is experiencing a cultural resurgence: in Instagram reels, viral songs, and comedy sketches—alive, unfiltered, and unapologetically local. Urdu, in contrast, is increasingly confined to curated spaces: ghazal nights, ornate wedding cards, nostalgia-driven festivals like Jashn-e-Rekhta or the Urdu Festival in Bhendi Bazaar but celebrating a language three days a year is not enough. Urdu is not just losing cultural currency—it is fading into silence. Yet, my parents still write grocery lists in Urdu; my father still recites Faiz when the headlines feel too heavy. I still hope our children will one day read the letters we never wrote. Because language, like love, does not vanish—it lingers, waits, and quietly hopes to be heard again.</h1>

<h1 class="full">When my friend, who teaches Politics at King's College London, tried to set me up with a finance guy studying at LSE, I never expected our first phone call to turn into a linguistic revelation. "It would be so romantic to have my partner read Urdu novels to me," he mused. His confidence caught me off guard. Here was a Dakhni Muslim man, effortlessly fluent in a dialect I had never fully encountered, yet unable to read the Lucknowi Urdu I had always considered my own. I had long believed I was proficient in Urdu—until he asked me to switch from English to Urdu. That simple request exposed a truth I had been ignoring: my grasp of the language had slipped. While my bond with my mother tongue has been tenuous, my relationship with love has never felt stronger. That LSE guy? He’s now my fiancé.</h1>

<h1 class="full">If there’s one thing I have come to understand, it’s that love finds you—but only when the timing and place are just right. For us, it wasn’t just romantic chemistry; it was a shared curiosity about languages, cultures, and traditions. Early in our courtship, we spoke about the languages we knew, struggled with, and hoped to learn together. I’d read to him from Asrar-e-Khudi, which he had only read in English, but longed to experience in Urdu. In return, he introduced me to Dakhni, teaching me idioms, couplets, and slang. He’s now in Bengaluru, managing his family business; I’m in Edinburgh, finishing a PhD. Some mornings, I wake with an image of us reading to each other. Even if life gives us little, we’ll have that—our shared love for reading. My mother laughs, but the idea only deepens my resolve to reclaim my hold on Urdu.</h1>

<h1 class="full">As a language, Urdu flourished in India until the late 1980s, but has been steadily declining, and like many third-generation speakers, I had unknowingly distanced myself from my linguistic heritage. The dominance of English and Western cultural influences had eroded the everyday presence of Urdu in my life. While I thought I had Urdu in my bones—until these conversations with my fiancé, I suddenly felt the weight of what I had lost. Determined to reclaim it—and, if I'm being honest, to impress him—I called my father and asked if he would be my Urdu tutor. Thus began my journey of rediscovering my mother tongue.</h1>

<h1 class="full">My father, now in his seventies, a retired regional auditor and a lawyer by academic training, was touched. “Urdu is just like that vine in our ancestral home”, he mused. “Still alive. But barely.” As I tried to polish my everyday Urdu, he mourned the language's grand decline—one he had witnessed firsthand. Once the language of tehzeeb (refinement) and akhlaq (ethics), Urdu was not just a language but a bridge across diverse communities. Ishtiaq H. Qureshi noted, "While Persian remained the official language of the Mughal court, Urdu became the language of everyday use for intercommunication among the different communities regardless of their creed…" (1977, p. 101), cementing its role as a primary language in South Asia.</h1>

<h1 class="full">While details can be murky, there is some evidence that Urdu held official status in British India alongside English. But in post-independence India, the language began to slip from public consciousness, even as it held official status in states like Uttar Pradesh. Today, its presence feels ghostly—familiar yet fading. In the increasingly polarised world we currently reside in, Urdu is not just losing its cultural significance but becoming increasingly obsolete. My father laments the time when Urdu was not exotic—it was everywhere. It adorned newspapers, advertisements, literary and cultural magazines, film posters, love letters, and shopfronts; a language of courtrooms, conversation, and community.</h1>

<h1 class="full">He particularly reminisces about when brand adverts in North India would appear in both Hindi and Urdu. He recalls full-page spreads in Urdu newspapers and magazines—ads that paired glamorous film stars like Madhubala, Rekha, or a young Amitabh Bachchan with elegantly calligraphed Urdu slogans. After looking through some of the archives myself, I found that brands like Lux, with their celebrity-studded campaigns, were often advertised as "filmi sitaaron ka husn bakhsh saabun", promising the secret to star-like beauty. The poetics of the language made an everyday product, as small as a soap, aspirational. He gets nostalgic about the old Bata campaigns. Still a teenager then, he would compare those shoes to today’s Loro Piana—as if owning a pair meant you had truly arrived.</h1>

<h1 class="full">What stays with me, though—perhaps it’s the architect and designer in me—is the sheer beauty of those adverts. There’s something about the black-and-white aesthetic, the sleekness of hand-drawn flourishes, the floral typefaces. They had restraint, grace, and a kind of quiet confidence—very different from the overproduced visuals we see now. Everything looked intentional. Even when the product was as simple as a bar of soap, the ad carried a kind of elegance you don’t find in the hyper-saturated, over designed templates of today. For my father, however, it was never just about the product or the advert. It was about the language, the way Urdu once held a significant space in the public imagination.</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Urdu:

حسین نرملا کا محافظ جلد لکس ٹوائلٹ صابن ہے

لکس ٹوائلٹ صابن

فلمی ستاروں کا حسن بخش صابن</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Roman Urdu:

Haseen Nirmala ka muhafiz jild hai Lux toilet sabun

Lux toilet sabun

Filmi sitaaron ka husn bakhsh saabun</h1>

<h1 class="full">

English:

Lux toilet soap is the protector skin of beautiful Nirmala

Lux Toilet Soap

The beauty-bestowing soap of film stars</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Urdu:

"لَکس کو میں اب اور بھی پسند کرنے لگی ہوں...

"!کتنی دلفریب ہے اس کی نئی خوشبو

ہیما مالنی—

لکس — فلمی ستاروں کا خالص، نرم صابن</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Roman Urdu:

"Lux ko main ab aur bhi pasand karne lagi hoon...

kitni dilfareeb hai iski nayi khushboo."

— Hema Malini

Lux — filmee sitaaron ka khaalis, naram saabu</h1>

<h1 class="full">

English:

"I’ve started liking Lux even more now...

its new fragrance is simply enchanting."

— Hema Malini

Lux — the pure, gentle soap of film stars</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Urdu:

ایمبیسیڈر

خوش وضع جوتے

ممتاز آدمیوں کے لیے

خوش وضع بَلو سرکٹ جوتے — کیچڑ سے

محفوظ رکھنے والا اگلا حصہ — آرام دہ

ملائم، کاف کا اَپر — سیاہ یا بادامی

رنگوں میں — چمڑے کا تَلا</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Roman Urdu:

Ambassador

Khush-wazaa jootay

Mumtaz aadmiyon ke liye

Khush-wazaa Blu Circuit jootay — kichad se

Mahfooz rakhne waala agla hissa — aaram deh

Mulaayam, kaaf ka upper — siyaah ya baadami

Rangon mein — chamray ka tala</h1>

<h1 class="full">

English:

Ambassador

Elegantly designed shoes

for distinguished men.Elegantly designed Blu Circuit shoes — protected against mud

A front section built for safety — and comfort

Soft, with a 'Kaaf-style' upper — in black or tan

Available in shades — with a leather sole</h1>

<h1 class="full">Although some Urdu newspaper titles are still circulating, once-ubiquitous brands like Lux, Ponds and Pears, once regulars in Urdu newspapers, have stopped marketing in Urdu. That lyrical branding—once so common, so comforting—has quietly disappeared. Brands no longer advertise in Urdu not because it does not sell, but because it has become politically inconvenient. A 2021 FabIndia Diwali ad, which refers to the name of their Diwali collection, Jashn-e-Riwaaz, a phrase that means "celebration of tradition" in Urdu, faced backlash for being "culturally inappropriate"—a reminder of how weaponised language politics has become.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Cinema, too, turned away. My father mentions that until the 1980s, Bollywood film posters were trilingual—Hindi, English, and Urdu—that spoke to India's plural identity. What intrigues me most about these film posters is their hand-painted aesthetic—bold, eclectic colours, ornate designs, and, of course, the linguistic inclusivity. But by 1989, Urdu had all but vanished. Take Ram Lakhan, released in January: the main title sequence still featured all three languages. Contrast it with Maine Pyar Kiya, released in December that year, which marked Urdu's erasure from mainstream cinema visuals. The reasons were many: rising tensions with the neighboring country, shrinking numbers of Urdu-speaking screenwriters, and changing audience demographics.</h1>

<h1 class="full">On the other hand Dakhni, which may have faded from literary prominence over the past 80 years due to a lack of official patronage, continues to thrive as a spoken dialect of Urdu across South India. The key distinction lies in usage: people converse in Dakhni, but write in standard Urdu. Its survival owes much to its local speakers as well as to Deccani films and stage dramas, which gained immense popularity in the early 2000s, and more recently, to social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok. Interestingly, Dakhni adapts itself to the local linguistic landscape: Chennai Dakhni blends with Tamil, Bangalore Dakhni aligns with Kannada, and Hyderabad Dakhni draws heavily from Telugu.</h1>

<h1 class="full">My fiancé has introduced me to a range of slapstick Deccani movies and dramas that became cultural phenomena in the South. Titles like The Angrez, Hyderabadi Nawabs I & II, Gullu Dada Returns, and Gangs of Hyderabad are films we've attempted to watch together over FaceTime as a way to understand the local flavour of Dakhni culture. Though the dialogue is entirely in Dakhni, the posters and marketing materials are often in English—a telling detail about their targeted appeal. The Angrez, in particular, and one of its characters, Saleem Pheku, found a significant following not just among local audiences but also within the South Indian diaspora in the Middle East, UK and the USA.</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Dakhni Urdu (as spoken):

Poison boley toh scent ko boltey. Baahar milta.

– Saleem Pheku, The Angrez</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Standardised urdu script (with Dakhni style preserved):

پوئزن بولے تو سینٹ کو بولتے۔ باہر ملتا۔

– سلیم فیکو، دی انگریز</h1>

<h1 class="full">

English Translation:

"Poison, as in, that's what we call scent. You get it abroad."

– Saleem Pheku, The Angrez</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Dakhni Urdu (as spoken):

Aisich kaam karey toh apan popular hotey</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Standardised urdu script (with Dakhni style preserved):

ایسچ کام کرے تو اپن پاپولر ہوتے

Note: "اپن" (apan) = "ہم" (hum) in standard Urdu, used casually in Dakhni to mean "we / I (humble)".</h1>

<h1 class="full">

English Translation:

If we worked like this, we'd become popular.</h1>

<h1 class="full">

---</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Bengaloor ki Daastan by Pasha</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Dakhni Urdu (as spoken):</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Bengaloor ki daastan, suni toh hogi aapne

Maarte so faile aur baat karte baadme

Dil ke saaf khaali apni baat mech maghroor hame

Ek jigra, dusra daring, yeh do cheezan se mashoor hame</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Ghafoor hame, sabme bade lekin soch chotich

Seeda kya b dikta nai khaali dikhte note-ich

Ek pantar aaji baaji chaar-paanch showpiece

Ki kati iska bawa MLA uska bawa Police</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Hero khudke vaste, dusryan ku villain hume

Daaru peete nai, pilate pooryan ku chillum hame

Rupay kya cheez Dubai jaako kamalinge Dirham

Apne area mein sher, picche gully mein hiran hame</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Standard Urdu Script (with Dakhni style preserved):</h1>

<h1 class="full">

بنگلور کی داستان سنی تو ہوگی آپ نے

مارنے والے تو بہت ہیں، بات کرتے بعد میں

دل کے صاف، خالی، اپنی بات میں مغرور ہم

ایک جگر والا، دوسرا دلیر، یہی دو چیزیں ہمیں مشہور کرتی ہیں</h1>

<h1 class="full">

غفور ہم، سب میں بڑے لیکن سوچ چھوٹی

سیدھا کیا دکھتا ہے، خالی دکھتے ہیں نوٹ

ایک پتھر آج بازی، چار پانچ شو پیس

کہتے ہیں اس کا باوا ایم ایل اے، اس کا باوا پولیس</h1>

<h1 class="full">

ہیرو خود کے واسطے، دوسروں کو ولن ہم

شراب پیتے نہیں، پلانے والے پورے چِلّم ہم

روپے کیا چیز، دبئی جا کے کمائیں گے درہم

اپنے علاقے میں شیر، پیچھے گلی میں ہرن ہم</h1>

<h1 class="left">

English Translation:</h1>

<h1 class="full">

You must have heard the tale of Bangalore,

Many are quick to fight, but talk comes afterward.

With a pure and empty heart, proud of our own words,

One with courage, the other daring—these two traits make us famous.</h1>

<h1 class="full">

We are Ghafur, great among all but with small thoughts,

What appears straightforward is not; only the money is visible.

One stone today, four or five showpieces,

They say his father is the MLA, his father the police.</h1>

<h1 class="full">

We are heroes for ourselves, villains to others,

We don’t drink alcohol, but those who serve it smoke chillum fully.

What are rupees? We’ll earn Dirhams by going to Dubai,

In our area, we are lions; behind in the alley, we are deer.</h1>

<h1 class="full">In mainstream media, actor Mehmood Ali popularised Dakhni lingo in the early '90s, though much of the cinematic use of the dialect has been confined to comedy, contrary to the romanticised appeal of Urdu. However, in recent years, social media and the rise of Desi hip-hop have shifted the perception of Dakhni. Artists like Mohammad Affan Pasha, whose rap lyrics are rooted in everyday street Dakhni and far removed from parody, are helping reclaim the dialect as something more textured and authentic. Stand-up comedians still rely on its comic potential, but Dakhni is slowly beginning to express a broader cultural and emotional range. While its so-called dialect thrives in the streets, homes, music, and everyday life of the locals, my father mourns the gradual disappearance of Lakhnavi Urdu.</h1>

<h1 class="full">He particularly shares his quiet nostalgia for the days when he would write letters in Urdu—something he hardly gets to do anymore, thanks to the digital age. He remembers his letters to my mother from when they got stuck in their hometowns a few weeks after their wedding, due to the 1980s curfew in Western Uttar Pradesh. Delicate, handwritten, dipped in a sense of (be)longing and now replaced with FaceTime and WhatsApp. "There is no such firaaq (separation) anymore," my mother smirks. Romance, in its classic Urdu form, does not translate well on digital screens. My fiancé and I joke about it too—we are continents apart, yet never more than a tap away. And anyway, despite being fluent in Arabic, the Urdu script still feels alien to him. So writing Urdu letters to him will remain a dream.</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Urdu:

شامِ غم کچھ اُس نگاہِ ناز کی باتیں کرو

بے خودی بڑھتی چلی ہے راز کی باتیں کرو</h1>

<h1 class="full">

یہ سکوتِ ناز، یہ دل کی رگوں کا ٹوٹنا

خاموشی میں کچھ شکستِ ساز کی باتیں کرو</h1>

<h1 class="full">

نکہتِ زلفِ پریشاں، داستانِ شامِ غم

صبح ہونے تک اسی انداز کی باتیں کرو</h1>

<h1 class="full">

کچھ قفس کی تیلیوں سے چھن رہا ہے نور سا

کچھ فضا، کچھ حسرتِ پرواز کی باتیں کرو</h1>

<h1 class="full">

جس کی فُرقت نے پلٹ دی عشق کی کایا فراق

آج اُسی عیشِ نفسِ دم ساز کی باتیں کرو</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Roman Urdu:

Shaam-e-gham kuchh us nigah-e-naaz ki baatein karo

Bekhudi barhti chali hai, raaz ki baatein karo</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Yeh sukoot-e-naaz, yeh dil ki ragon ka tootna

Khamoshi mein kuchh shikast-e-saaz ki baatein karo</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Nekhat-e-zulf-e-parīshāñ, dāstān-e-shaam-e-gham

Subh hone tak usī andāz kī bāteñ karo</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Kuchh qafas ki teeliyon se chhan raha hai noor sa

Kuchh fiza, kuchh hasrat-e-parwaaz ki baatein karo</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Jis ki furqat ne palat di ishq ki kaaya Firaq

Aaj usi aish-e-nafas-e-dam-saaz ki baatein karo</h1>

<h1 class="full">

English:

In this evening of sorrow, speak of that tender glance;

Ecstasy is rising—let's speak in the language of secrets.</h1>

<h1 class="full">

This graceful silence, this breaking of the heart’s veins—

In this quiet, speak of broken melodies.</h1>

<h1 class="full">

The fragrance of tangled hair, the tale of the sorrowful night—

Until morning comes, let such themes linger in our talk.</h1>

<h1 class="full">

Some light filters through the bars of the cage—

Speak of the air, speak of the yearning to fly.</h1>

<h1 class="full">

The one whose absence transformed the very essence of love, O Firaq—

Today, speak of the joy in the breath that echoes their presence.</h1>

<h1 class="full">The Urdu he can't read—Lucknavi, polished, poetic—is the one he wants our children to learn. Dakhni, his mother tongue, he fears is too raw, too unrefined, but my fiancé is not alone in this anxiety. Bengaluru-based rapper Pasha, who performs in Dakhni, has spoken of his discomfort speaking Dakhni in public, often switching to Hindi out of the fear of being ridiculed. Today, he stands proudly in his linguistic identity, using music to reclaim space and dismantle the shame once tied to Dakhni. Similarly, heritage storyteller and journalist Yunus Lasania has long pushed back against the notion that Dakhni is somehow lesser than Urdu or that it is language only suited for parody.</h1>

<h1 class="full">The binary—Hindi as the language of the masses, Lucknavi Urdu as sophisticated, Dakhni as raw—reveals deeper cultural anxieties. Do we always have to choose between eloquence and intimacy? Between nazakat and apnapan? The internet loves to argue: Is Dakhni a dialect or a language in its own right? Lasania sees this divide as a product of linguistic hegemony, particularly from the North, where Dakhni is viewed as Urdu’s lesser sibling. I argue otherwise: Dakhni, with its casual tone and local flavour, is rich in emotion. It speaks of homes, but it also speaks of humans. It is not lesser; it is just different. As I navigate this duality—researching Dakhni while preserving my Lucknavi heritage—I’ve come to realize that both languages are on the verge of fading.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Dakhni is experiencing a cultural resurgence: in Instagram reels, viral songs, and comedy sketches—alive, unfiltered, and unapologetically local. Urdu, in contrast, is increasingly confined to curated spaces: ghazal nights, ornate wedding cards, nostalgia-driven festivals like Jashn-e-Rekhta or the Urdu Festival in Bhendi Bazaar but celebrating a language three days a year is not enough. Urdu is not just losing cultural currency—it is fading into silence. Yet, my parents still write grocery lists in Urdu; my father still recites Faiz when the headlines feel too heavy. I still hope our children will one day read the letters we never wrote. Because language, like love, does not vanish—it lingers, waits, and quietly hopes to be heard again.</h1>