<h1 class="left">Headbanging to rap, a young girl sits in the dark, wearing the conventional hooded ensemble of a hacker. After quickly divesting her inquisitive mother, she picks up a mysterious call. “Did my account get recovered?” the caller asks – she types up a string of code and asserts, it’s done. That’s how the short film ‘Hijabi Hacker’ begins – in real life, our hacker is Alfisha, a sixteen-year-old high schooler from Shankarwadi in Mumbai, where a few Teach for India (TFI) fellows joined forces to set up Nazaria Arts Collective, right after the lockdown.</h1>

<h1 class="left">Alfisha got to know about Nazaria and how it trains young people in digital media and storytelling, from a TFI fellow who was tutoring her class – and so did her close friend Yazdaan, who also played her on-screen confidant and client, who loses his money in a building scam – something not infrequent in Mumbai. Watching him bamboozle insidious governmental forces, resulting in intense chase scenes, it’s hard to picture him as a shy kid who gave the co-founder of Nazaria, Riddhi Samarth, a hard time getting him to open up when she was a TFI fellow teaching his class. “I took admission in a BMC school after lockdown, as we had financial problems,” the eighteen-year-old explained, “I was a backbencher in my last school, and Riddhi didi asked why I was not talking to people. I wouldn’t talk to her as well and she decided, ‘Okay, if you’re shy, from today you’re the class monitor.” He couldn’t quite remain silent after that; he laughed.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">Now he’s unfazed when he’s rapping on the streets in ‘Basti ki Heera’ channelling his favourite rap artist Divine, or when people crowd around the streets, watching them film ‘hijabi hacker’. It was a role tailor-made for him, his friend and the director – Ikra – had said, pacifying him when she dropped the role upon him two days before filming. “She was like, ‘We are literally transferring your real-life personality on screen’,” he recalls. However, he also had his part-time gig at a medical store. “It was 7 – 8 hours, so it was kind of full-time only,” he rued, “I made my parents understand someone else will do a job, and this is a turning point in my life – so the next day, seedha set pein.” They were filming with the other Nazaria kids who were part of the Reimagine programme, where they got four months of film training, culminating with them coming up with a script and pitching it. Sandeep Keshari, a Youth Artist and facilitator at Nazaria recalled pitch day very clearly as he had worked on a draft of what would become his first queer film ‘…Could it Be?’ – which everyone liked so much that he was awarded movie tickets. “To ‘Mr. and Mrs. Mahi’ as it was playing then,” he said, adding another classmate, Shreya, had received a year-long MUBI subscription.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">Sandeep came up with the idea, said his co-writer, Vandana. “He thought we needed to make a film on queer romance,” she explained. It’s been a little more than a year with Nazaria for Sandeep, who felt the lack of queer narratives within his community. “I wanted to let them know it’s just as simple as love between two straights,” explained the sixteen-year-old, stunning me for a second with his simple reasoning, which takes years for some to internalise. In his film, two schoolboys gradually realise the potential of their blooming feelings for each other, over a poem scribbled in the back of a notebook. He had watched a lot of queer films like ‘Moonlight’ which gave him ideas on how to shoot and also, represent. “I criticised some,” he added cheekily, “I saw them because I don’t wanna make films like them.”</h1>

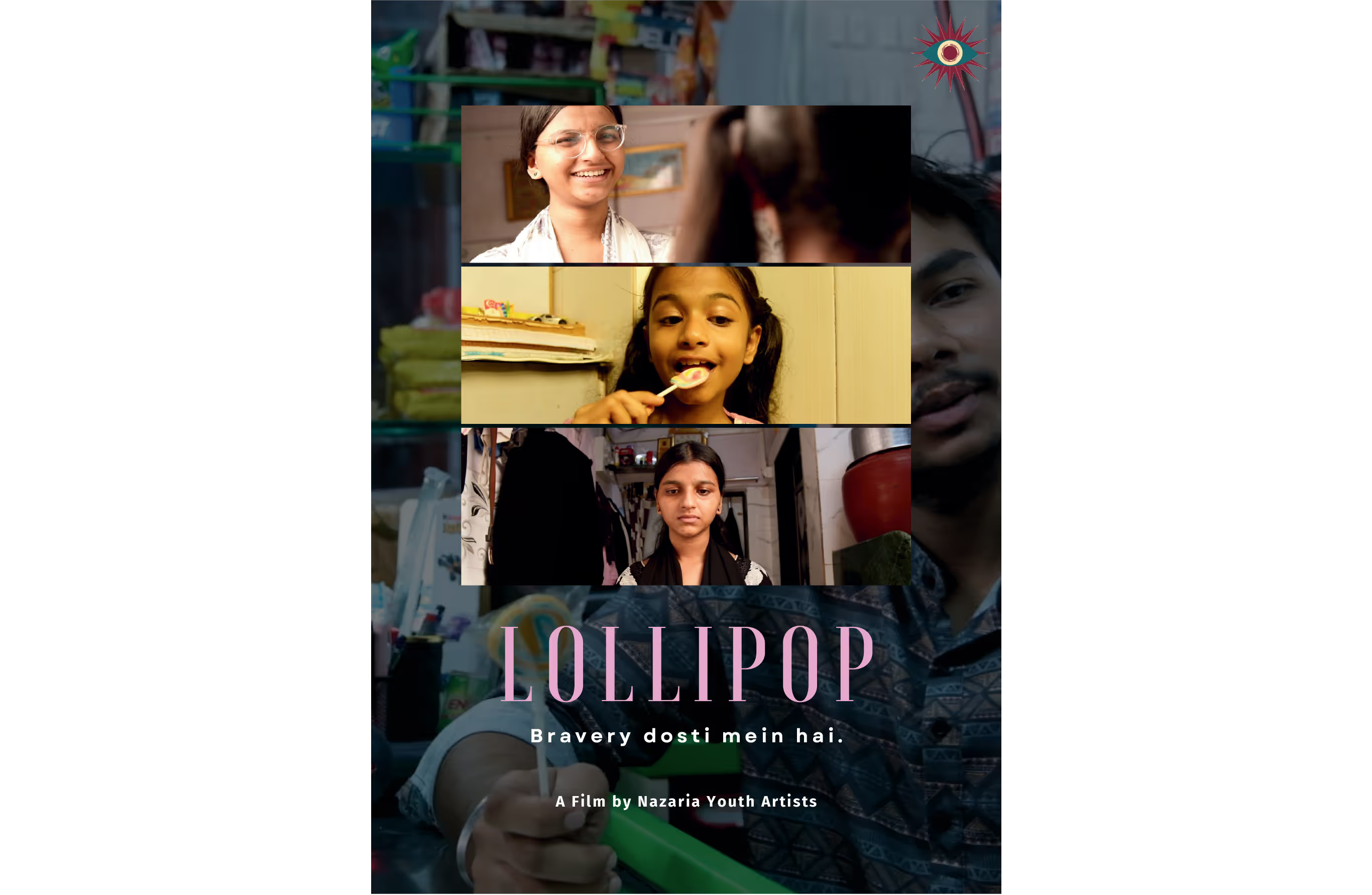

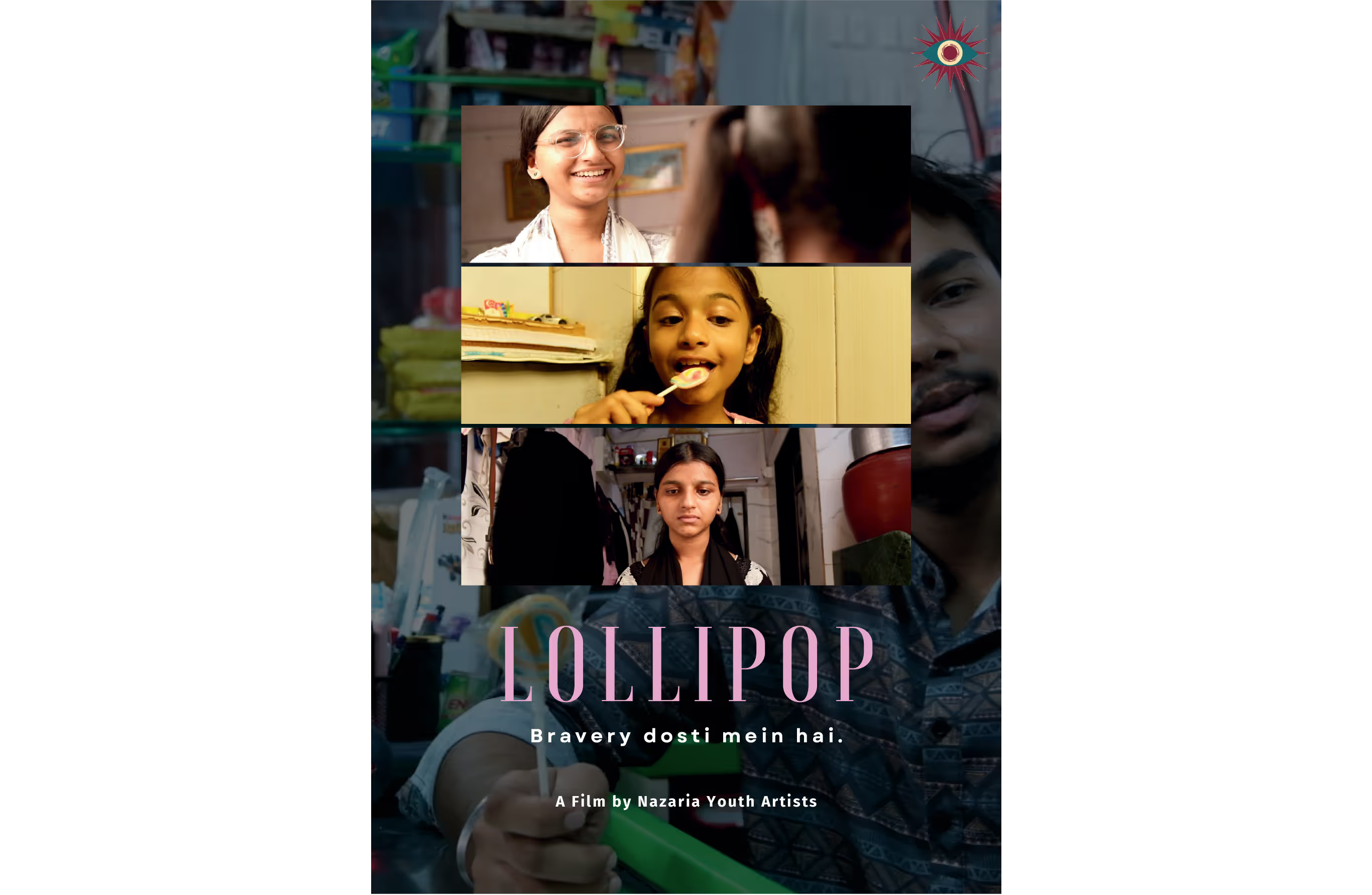

<h1 class="right">All the while Shreya filmed ‘Lollipop’, it rained consistently. “In the film, everyone’s hair is wet and there’s water everywhere,” she said, “But you get three days to shoot, so you have to manage with whatever is happening.” An added responsibility for her was working on a story of child abuse. One day, when they were discussing the meanings of power and gender, she suddenly recalled something she had witnessed in her childhood. “It was happening to one girl,” she said, “And I remember not wanting to go through that lane. I thought of making a film on it.” In the film, a pre-teen girl Chikki, is about to get assaulted by a shopkeeper when her friend intervenes; however, Shreya is also working on another level of religious discrimination. It stemmed from her own experience with her stern Hindu father, who refused to initially accept her Muslim friend.</h1>

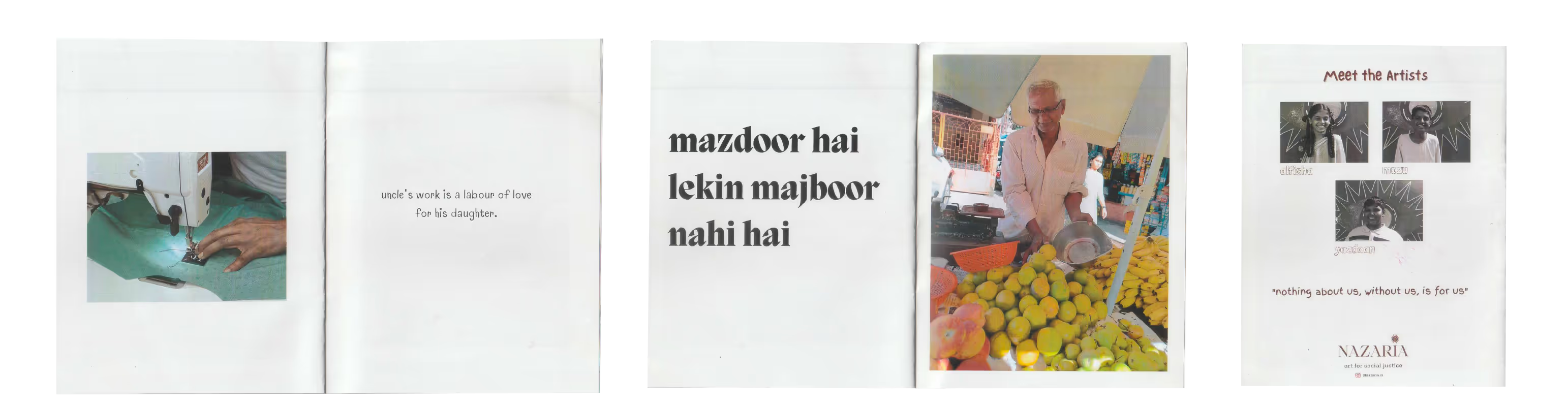

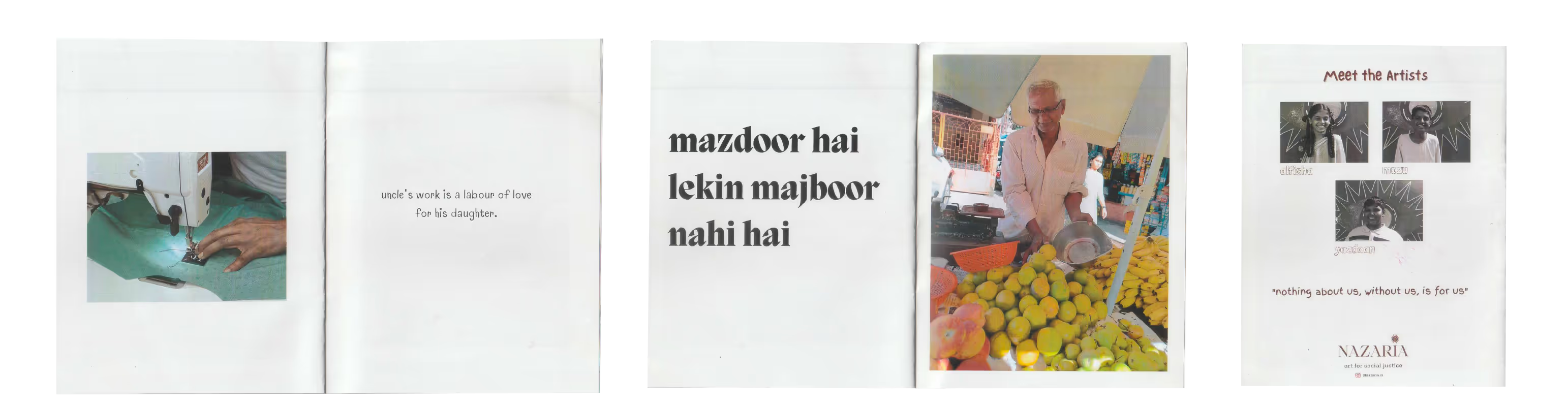

<h1 class="right">Religious intolerance, or rather, tolerance, was something Muzammil was also investigating in one of his earliest projects at Nazaria. That year, Eid and Diwali fell at the same time, and he came up with a zine where two Hindu and Muslim friends wrote about their experiences of celebrating Eid and Ganesh Chaturthi respectively – and polishing off all the food served at the festival. He hadn’t seen any discrimination around religious festivals around him at least, although last year thousands of policemen were stationed to maintain law and order during Ganesh Chaturthi. “Moreover, many of my Hindu and Christian friends meet during Eid and Diwali,” he added. There were others delving into stories in their own localities. Yazdaan teamed up with Muzammil and Alfisha to document the personal lives of daily wage workers, like the tailor on their street, or the newspaper man outside Nazaria’s Kahani Lab. “That was the first time we had to ask them for their consent and take the interviews,” recalled Alfisha, “At that time we hadn’t explored our community and were scared to ask people – what if they shout at us?” Once the interviews were compiled in the zine ‘Labour of Love’, in an effort to visibilise and therefore, valorise the labour they saw around them, they changed job descriptions to superhero titles. “The laundry guy became Iron Man as a metaphor,” laughed Yazdan, “And the tailor ‘sapno ko silne wala.”</h1>

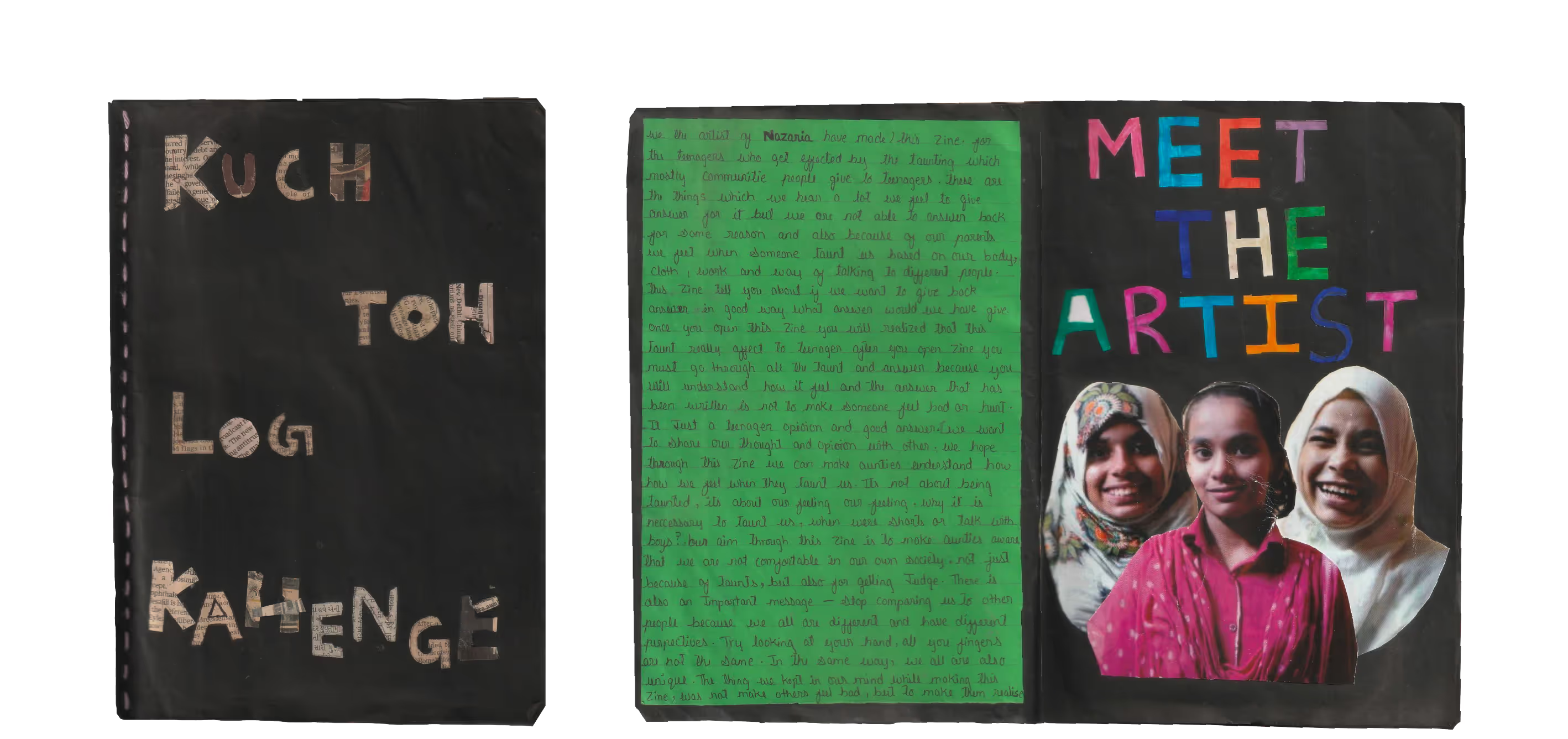

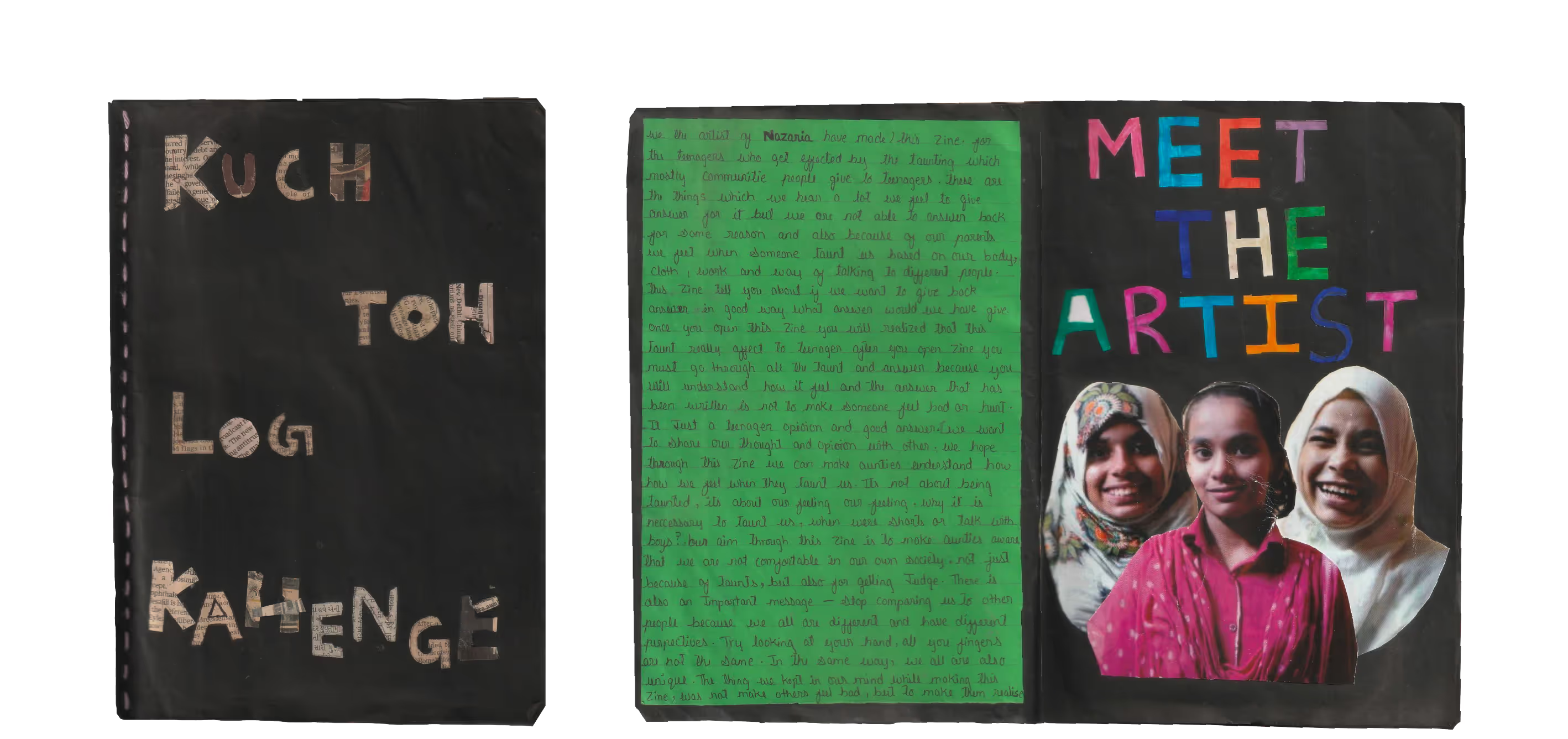

<h1 class="centre">For Alfisha, this was a way to express her frustration with the aunties in her community. “They always say something to me whenever I wear certain clothes or if I do something wrong,” she said, “Is this the right thing to do? So, with my friends Ikra and Hine, we decided to make it into a zine, which won’t make them feel bad but we would be able to express our feelings.” Indeed, the zine makes sure to mention that the intent was in no manner meant to hurt anyone, in a wordy introduction. Then the fun begins with fortune-cookie-like messages popping out of envelopes in the respective pages. Imagine an uncle asking you this, the zine urges: ‘Itne tyaar hoke kisse milne jaa rahe ho?’ The envelope below offers the snide answer, “Aapki bahu se’, implicating the sexualised gaze in the first place.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">“Until you know who you are, you won’t be able to do anything,” shrugged Yazdaan, who, before Nazaria, had thought the arts were for girls. “At Nazaria, I realised I had rights and a voice – and that I had capabilities.” Many children from lower-income backgrounds can access art, which they wouldn’t even have thought of previously, Sandeep reflects. and it was being able to work with the studio-grade professional equipment that Muzammil loved most, which ultimately drew him to cinematography. Yazdaan recalled the moment of amazement when he stepped into a recording studio to sing the rap for ‘Basti ka Heera’, which asserted the power of youngbloods from the basti, which he wrote with his friends Sufiyan and Yahya, who have moved away now, he rued. “It was the month of Ramzan, and we were rapping while fasting,” he recalled fondly, “We broke our roza in the car while returning.”</h1>

<h1 class="left">They’re learning to make documentaries now and Sandeep clearly sees the difference between how Nazaria sees hard-core journalism, and how the mainstream media does with its fluffy reportage – which is perhaps why Muzammil would rather not get into a filmmaking school, even though Nazaria will ensure he gets a scholarship – he’s apprehensive he might not have the same kind of mentorship there, more so as Nazaria follows the TFI teaching method focusing on more engaged learning. It’s really a safe space, Sandeep reflected. After completing their films, they all embarked on internships in media houses like Chalk & Cheese, Civic Studio and Harkat Studios. “We get brand video projects now,” said Sandeep, “And everything is paid.” Vandana has gone ahead and enrolled herself in Mass Media and Communication while her and Sandeep’s film travelled from Abu Dhabi, Columbia and now to KASHISH Film Festival, she gushed excitedly. Sandeep dreams of applying to film school next year. “Unfortunately, I took science in high school,” he chuckled, “If I were part of Nazaria before, I would never have chosen that!”</h1>

<h1 class="left">You can support the Nazaria Collective via Milaap</h1>

<h1 class="left">Photography by Sapan Taneja and Tia Chinai</h1>

<h1 class="full">Headbanging to rap, a young girl sits in the dark, wearing the conventional hooded ensemble of a hacker. After quickly divesting her inquisitive mother, she picks up a mysterious call. “Did my account get recovered?” the caller asks – she types up a string of code and asserts, it’s done. That’s how the short film ‘Hijabi Hacker’ begins – in real life, our hacker is Alfisha, a sixteen-year-old high schooler from Shankarwadi in Mumbai, where a few Teach for India (TFI) fellows joined forces to set up Nazaria Arts Collective, right after the lockdown.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Alfisha got to know about Nazaria and how it trains young people in digital media and storytelling, from a TFI fellow who was tutoring her class – and so did her close friend Yazdaan, who also played her on-screen confidant and client, who loses his money in a building scam – something not infrequent in Mumbai. Watching him bamboozle insidious governmental forces, resulting in intense chase scenes, it’s hard to picture him as a shy kid who gave the co-founder of Nazaria, Riddhi Samarth, a hard time getting him to open up when she was a TFI fellow teaching his class. “I took admission in a BMC school after lockdown, as we had financial problems,” the eighteen-year-old explained, “I was a backbencher in my last school, and Riddhi didi asked why I was not talking to people. I wouldn’t talk to her as well and she decided, ‘Okay, if you’re shy, from today you’re the class monitor.” He couldn’t quite remain silent after that; he laughed.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Now he’s unfazed when he’s rapping on the streets in ‘Basti ki Heera’ channelling his favourite rap artist Divine, or when people crowd around the streets, watching them film ‘hijabi hacker’. It was a role tailor-made for him, his friend and the director – Ikra – had said, pacifying him when she dropped the role upon him two days before filming. “She was like, ‘We are literally transferring your real-life personality on screen’,” he recalls. However, he also had his part-time gig at a medical store. “It was 7 – 8 hours, so it was kind of full-time only,” he rued, “I made my parents understand someone else will do a job, and this is a turning point in my life – so the next day, seedha set pein.” They were filming with the other Nazaria kids who were part of the Reimagine programme, where they got four months of film training, culminating with them coming up with a script and pitching it. Sandeep Keshari, a Youth Artist and facilitator at Nazaria recalled pitch day very clearly as he had worked on a draft of what would become his first queer film ‘…Could it Be?’ – which everyone liked so much that he was awarded movie tickets. “To ‘Mr. and Mrs. Mahi’ as it was playing then,” he said, adding another classmate, Shreya, had received a year-long MUBI subscription.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Sandeep came up with the idea, said his co-writer, Vandana. “He thought we needed to make a film on queer romance,” she explained. It’s been a little more than a year with Nazaria for Sandeep, who felt the lack of queer narratives within his community. “I wanted to let them know it’s just as simple as love between two straights,” explained the sixteen-year-old, stunning me for a second with his simple reasoning, which takes years for some to internalise. In his film, two schoolboys gradually realise the potential of their blooming feelings for each other, over a poem scribbled in the back of a notebook. He had watched a lot of queer films like ‘Moonlight’ which gave him ideas on how to shoot and also, represent. “I criticised some,” he added cheekily, “I saw them because I don’t wanna make films like them.”</h1>

<h1 class="full">All the while Shreya filmed ‘Lollipop’, it rained insistently. “In the film, everyone’s hair is wet and there’s water everywhere,” she said, “But you get three days to shoot, so you have to manage with whatever is happening.” An added responsibility for her was working on a story of child abuse. One day, when they were discussing the meanings of power and gender, she suddenly recalled something she had witnessed in her childhood. “It was happening to one girl,” she said, “And I remember not wanting to go through that lane. I thought of making a film on it.” In the film, a pre-teen girl Chikki, is about to get assaulted by a shopkeeper when her friend intervenes; however, Shreya is also working on another level of religious discrimination. It stemmed from her own experience with her stern Hindu father, who refused to initially accept her Muslim friend.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Religious intolerance, or rather, tolerance, was something Muzammil was also investigating in one of his earliest projects at Nazaria. That year, Eid and Diwali fell at the same time, and he came up with a zine where two Hindu and Muslim friends wrote about their experiences of celebrating Eid and Ganesh Chaturthi respectively – and polishing off all the food served at the festival. He hadn’t seen any discrimination around religious festivals around him at least, although last year thousands of policemen were stationed to maintain law and order during Ganesh Chaturthi. “Moreover, many of my Hindu and Christian friends meet during Eid and Diwali,” he added. There were others delving into stories in their own localities. Yazdan teamed up with Muzammil and Alfisha to document the personal lives of daily wage workers, like the tailor on their street, or the newspaper man outside Nazaria’s Kahani Lab. “That was the first time we had to ask them for their consent and take the interviews,” recalled Alfisha, “At that time we hadn’t explored our community and were scared to ask people – what if they shout at us?” Once the interviews were compiled in the zine ‘Labour of Love’, in an effort to visibilise and therefore, valorise the labour they saw around them, they changed job descriptions to superhero titles. “The laundry guy became Iron Man as a metaphor,” laughed Yazdan, “And the tailor ‘sapno ko silne wala.”</h1>

<h1 class="full">For Alfisha, this was a way to express her frustration with the aunties in her community. “They always say something to me whenever I wear certain clothes or if I do something wrong,” she said, “Is this the right thing to do? So, with my friends Ikra and Hine, we decided to make it into a zine, which won’t make them feel bad but we would be able to express our feelings.” Indeed, the zine makes sure to mention that the intent was in no manner meant to hurt anyone, in a wordy introduction. Then the fun begins with fortune-cookie-like messages popping out of envelopes in the respective pages. Imagine an uncle asking you this, the zine urges: ‘Itne tyaar hoke kisse milne jaa rahe ho?’ The envelope below offers the snide answer, “Aapki bahu se’, implicating the sexualised gaze in the first place.</h1>

<h1 class="full">“Until you know who you are, you won’t be able to do anything,” shrugged Yazdaan, who, before Nazaria, had thought the arts were for girls. “At Nazaria, I realised I had rights and a voice – and that I had capabilities.” Many children from lower-income backgrounds can access art, which they wouldn’t even have thought of previously, Sandeep reflects. and it was being able to work with the studio-grade professional equipment that Muzammil loved most, which ultimately drew him to cinematography. Yazdan recalled the moment of amazement when he stepped into a recording studio to sing the rap for ‘Basti ka Heera’, which asserted the power of youngbloods from the basti, which he wrote with his friends Sufiyan and Yahya, who have moved away now, he rued. “It was the month of Ramzan, and we were rapping while fasting,” he recalled fondly, “We broke our roza in the car while returning.”</h1>

<h1 class="full">They’re learning to make documentaries now and Sandeep clearly sees the difference between how Nazaria sees hard-core journalism, and how the mainstream media does with its fluffy reportage – which is perhaps why Muzammil would rather not get into a filmmaking school, even though Nazaria will ensure he gets a scholarship – he’s apprehensive he might not have the same kind of mentorship there, more so as Nazaria follows the TFI teaching method focusing on more engaged learning. It’s really a safe space, Sandeep reflected. After completing their films, they all embarked on internships in media houses like Chalk & Cheese, Civic Studio and Harkat Studios. “We get brand video projects now,” said Sandeep, “And everything is paid.” Vandana has gone ahead and enrolled herself in Mass Media and Communication while her and Sandeep’s film travelled from Abu Dhabi, Columbia and now to KASHISH Film Festival, she gushed excitedly. Sandeep dreams of applying to film school next year. “Unfortunately, I took science in high school,” he chuckled, “If I were part of Nazaria before, I would never have chosen that!”</h1>

<h1 class="full">You can support the Nazaria Collective via Milaap</h1>

<h1 class="full">Photography by Sapan Taneja and Tia Chinai</h1>