<h1 class="centre">In the last few years, disco–a music genre characterised by its electronic, glassy sounds, reverberating vocals and use of synthesisers–has come to represent something bigger than itself: a nostalgic longing for a simpler, better time. An era in which we could be young, wild and free. The early seventies in the USA saw disco being birthed from this very quest for freedom. It was always political, a counterculture heralded by queer, black and Latino communities in a time when there were still laws against homosexual behaviour in public. Dancing was considered shameful; dancing with partners of the same sex was illegal. Amidst this emerged hip thrusting moves, bodies vibrating together, sex in bathroom stalls, exit stairwells. Disco was inherently erotic, hedonistic, centred around non-phallic pleasure and sexual liberation. Unemployment, inflation, race riots and crime was on the rise. A growing sense of disillusionment and despair ushered in the age of disco: a rebellion, a collectivist escape, a sexual revolution for outcasts.</h1>

<h1 class="left">This style of music burst into India with a 15 year-old Nazia Hassan crooning ‘Aap Jaisa Koi’ for Qurbani (1980). On screen, Zeenat Aman, a single ruby rose in her hair, swayed to the track in a sparkling bloodred cut-out dress. Hassan instantly became synonymous with the genre: in the next few years, she would go on to release smash hits ‘Disco Deewane’ and ‘Boom Boom’, both album singles, with her brother Zoheb. Both records–and ‘Aap Jaisa Koi’–were composed by Bangalore-born, London-based Biddu Appaiah, a pioneer of disco in Europe and India. In the USA, Mumbai-born Asha Puthli had long been working on genre-defying records that disco would eventually descend from.</h1>

<h1 class="left">“They were some of the key innovators of disco as we know it in the West,” reveals Raghav Mani, co-founder of Naya Beat, a label that works to revive forgotten South Asian dance and electronic music. Most notably, Naya Beat restored and reissued Mohinder Kaur Bhamra and Kuljit Bhamra’s long-lost 1982 album Punjabi Disco and are leading the revival of Puthli’s legacy through the release of remix EPs like Disco Mystic (2023) and an international tour, her first in 44 years. “In New York City, Asha Puthli created seminal pre-disco records like The Devil is Loose and 1001 Nights of Love. Biddu wound up in Europe, created the Eurodisco sound, and then brought that back with him in his work with Nazia and Zohaib. There’s a very interesting full-circle aspect to it all–these two Indian artists had a really important role to play in disco in the West, and then that was fed back into India.”</h1>

<h1 class="centre">By the time disco emerged in India, it had started to fade in the West. “The Bee Gees’ soundtrack album for Saturday Night Fever (1977) was probably the height of its commercial success. Then it went back underground and eventually evolved into a kind of boogie and electro-funk,” explains Mani. There were overtones of racism and homophobia in the backlash against this genre, which was dismissed by rock music fans as superficial and shallow and vanished almost overnight. In 1979, Steve Dahl–a DJ fired from his job at the radio station because they were planning to transition from rock to disco–invited listeners to Disco Demolition Night: 50,000 showed up; crates of disco records were blown up on a baseball field. In India, however, disco remained a part of mainstream Bollywood music from the late seventies to the mid eighties.</h1>

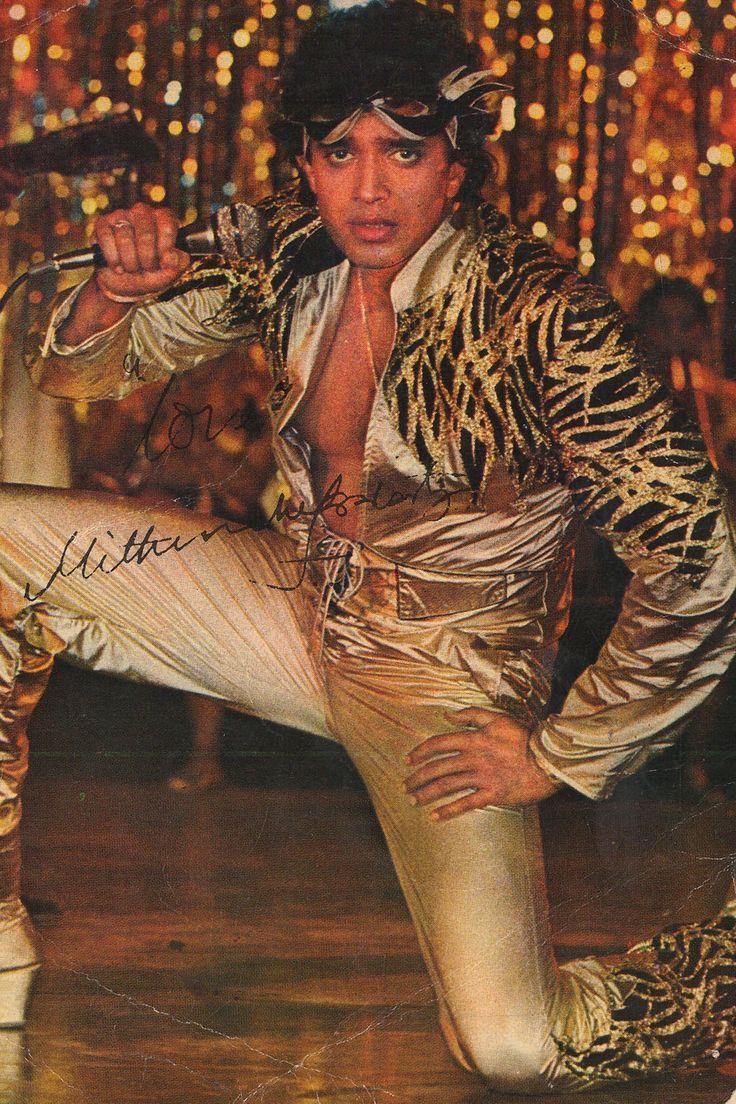

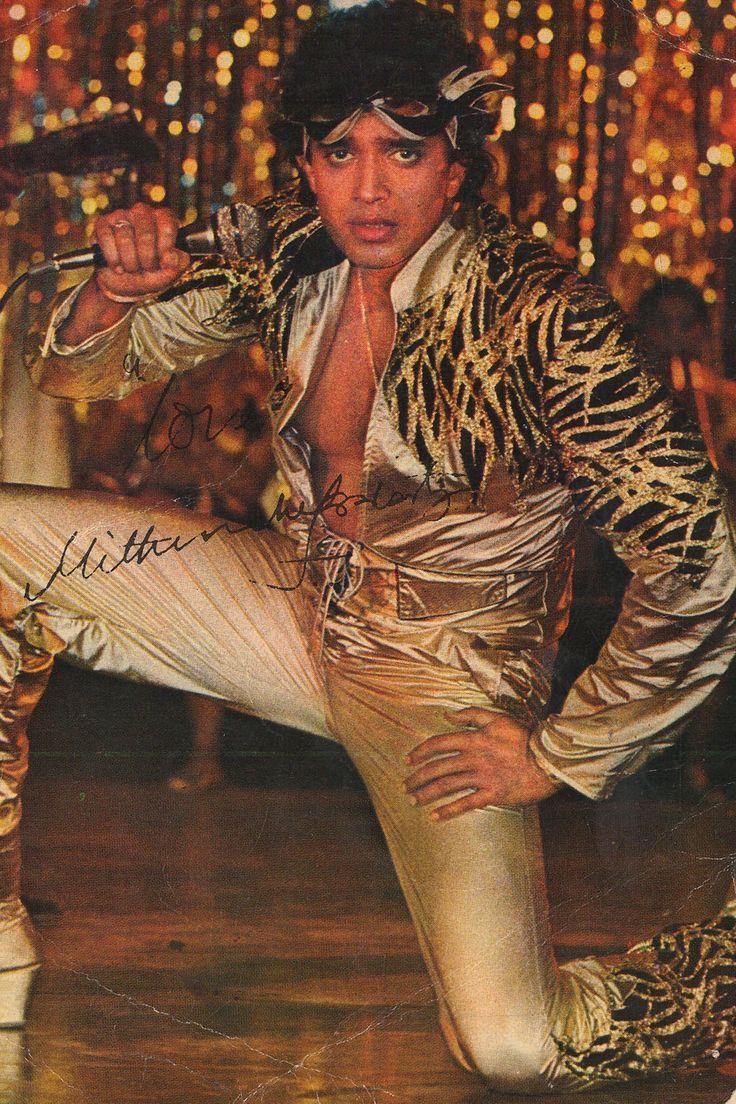

<h1 class="centre">This timing was significant. As in the USA, disco in India closely followed an oppressive political climate. The 21-month Emergency had only been revoked about two years before Bollywood’s disco fever, which was a call to liberation, cosmopolitanism and modernity: a cultural handover to the youth of the country. In his signature black sunglasses and heavy gold necklaces, Bappi Lahiri composed, produced (and sometimes plagiarised) many memorable tunes: the 1982 Disco Dancer album featuring ‘Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy Aaja’ which became a global sensation during the COVID-19 lockdown; ‘Jawani Janeman’, seductively sung by Asha Bhosle and brought to life by a gold-clad, glamourous Parveen Babi; ‘Disco Station’ , ‘Intehaan Ho Gayi’ and ‘Yaar Bina Chain Kaha Re.’ R.D. Burman refused to stay behind, composing ‘Yamma Yamma’, ‘Aa Dekhen Zara’ and ‘Jahan Teri Yeh Nazar Hai.’ Extravagant sets; flared, flowy bell bottoms to make dance easier; shiny headbands; all of Russia – where Hollywood was censored–drooling over Mithun Chakraborty in Disco Dancer. Unlike the West, where it was for those on the margins of society, Bollywood rebranded disco. It came to be associated with affluence: men in tuxedos–Feroz Khan, Shashi Kapoor–stoically gazing at women like Aman and Babi, ornamental, drenched in sequins, singing and dancing for them.</h1>

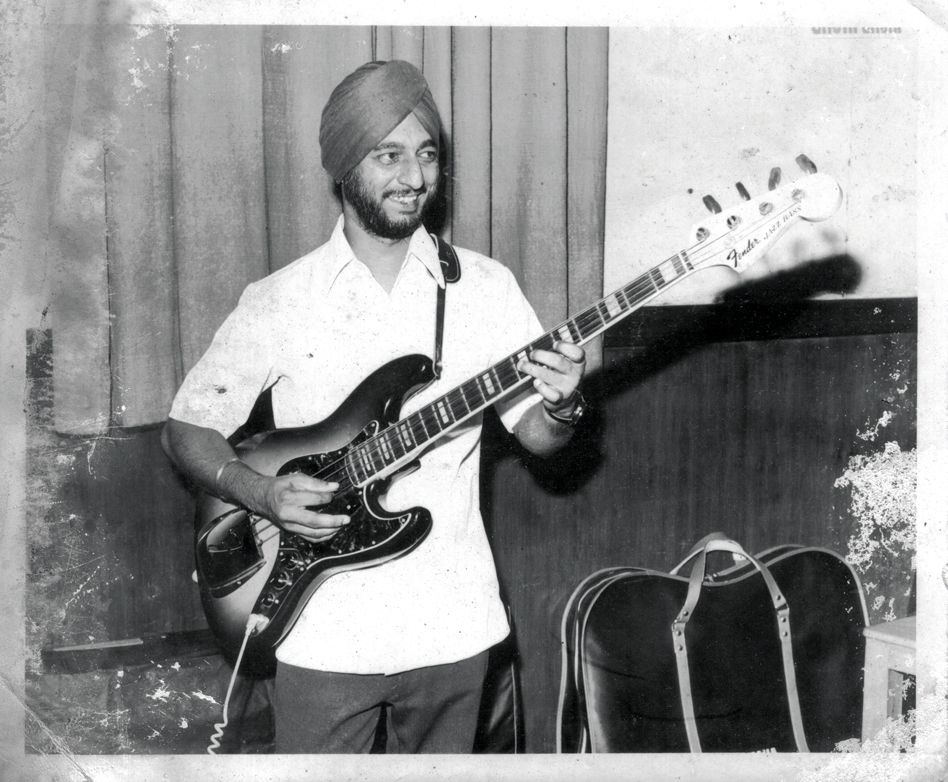

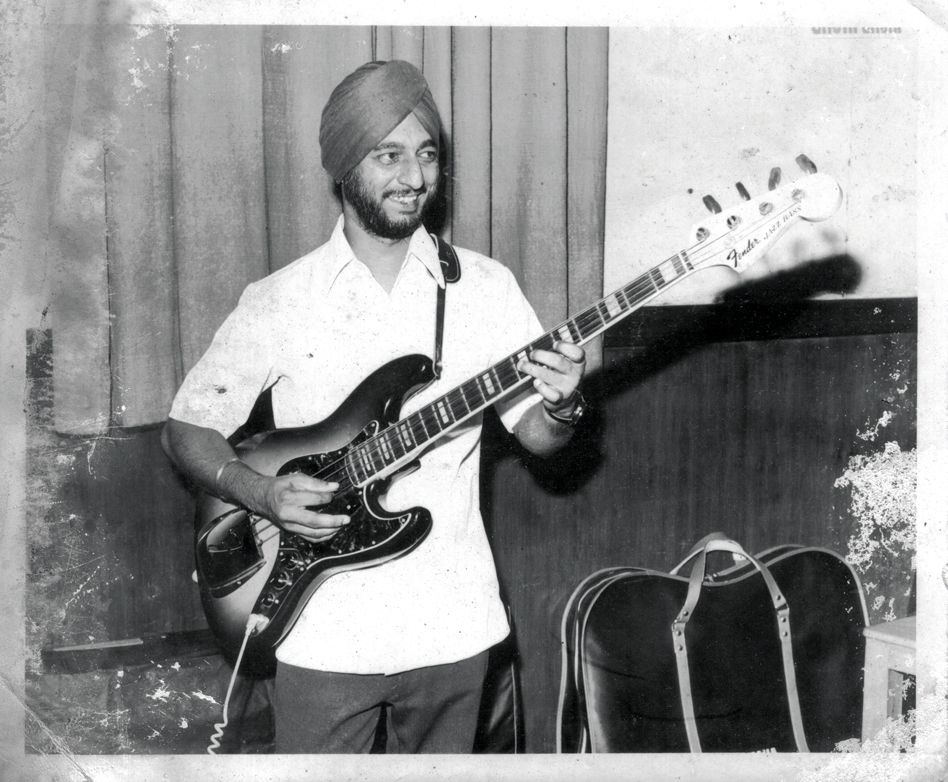

<h1 class="right">Still this subculture seeped into the crevices of India. For the masses, going to the disco became interchangeable with visiting a nightclub, going dancing. Lahiri’s experiments with synthesisers inspired composer Charanjit Singh to create Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat, accidentally inventing acid house in 1982. In the same year, diaspora albums like Punjabi Disco and Rupa Biswas’ Disco Jazz were created and largely disregarded. In his digging adventures, music archivist and record store owner Nishant Mittal has rediscovered countless obscure disco records that still remain mostly unknown: from Marathi disco and Sindhi disco to disco remakes of Indian prayers, disco-qawwali, Kannada language remakes of Hindi disco tracks, Oriya disco and more.</h1>

<h1 class="centre">“The great thing about Indian culture is that if we copy, we do it in an innovative way that reflects our culture and musical heritage,” notes Mani. “So an Indian disco soundtrack had many unique elements: there was more drama, more surprises. It was disco-inspired, not copycat disco.” As new technology like synths and drum machines grew popular in India, he adds, composers like R.D. Burman, Charanjit Singh and Bappi Lahiri stuck to the West’s rhythmic elements but “replaced entire lush string sections and horn sections with presets and instrumentations on these machines. This created a compelling new sound.”</h1>

<h1 class="centre">It was an era of transformation, of technological advancements that no common man could have imagined just a few decades ago. Man had now been on the moon. In the same year, musician Gita Sarabhai had introduced the synthesizer to India while her brother Vikram headed space research for the INCOSPAR. Disco urged us to look to the future; it advocated speed, technology and youth culture, inspired hope in a still newly independent India for whatever was coming. Space missions happening around the world “made humans wonder about the cosmos, the expanse of the universe and other living beings on other planets”, observes Anusha Vikram. This manifested not only in the futuristic, mechanical sounds of disco–laser, buzzy noises akin to spacecrafts–but also in the cosmic, almost dreamlike album art and lyrical themes accompanying this music. Take Nazia and Zoheb’s Star: a singer, lit by starlight, poses against the vast night sky. Disco Dancer (1982), Armaan (1981), Zamaane Ko Dikhana Hai (1981), all featured near-celestial beings against beaming lights.</h1>

<h1 class="left">Unlike the West, disco died quietly in India, replaced by other genres and styles of production like Indian pop. Occasional tracks in the 2000s–‘It’s the Time to Disco’ (2003), ‘Aaj Ki Raat’ (2006), SOTY’s ‘Disco Deewane’ remake (2012)–paid homage to the genre. But soon we realised that technology had failed to create the utopian world we had imagined it would, and this aesthetic, along with everything it represented, disappeared across the globe.</h1>

<h1 class="left">Except: only two weeks ago, Harry Styles announced his upcoming album: Kiss All the Time. Disco, Occassionally. More importantly, previously overlooked trailblazers are unexpectedly gaining the recognition they deserve: Charanjit Singh’s Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat is now almost mainstream, set to be reissued by American label Light in the Attic Records in June 2026. Punjabi Disco’s overwhelming success 44 years after its release has surprised and overwhelmed Kuljit Bhamra who notes the youth’s “renewed interest in the physical nature of listening to music and exploring how it’s been put together.” At the age of 69, Rupa Biswas released her second record since Disco Jazz and performed live for the first time in 30 years. At 70, Asha Puthli’s global tour is selling out. What to make of this return of disco except that it always seems to return when we need it the most? In times when government control tightens, censorship grows and fascism slowly rises. Disco, art, resurfaces, mixed with rebellion, with a quiet surge of hope. Inexplicably, we find ourselves gravitating towards the age-old ways in which we fought back, towards the impulse to reach again for the stars. Inevitably, history repeats itself. Inevitably, disco lets us escape. But more crucially, it helps us unite: to sing and dance again under the glitzy lights.</h1>

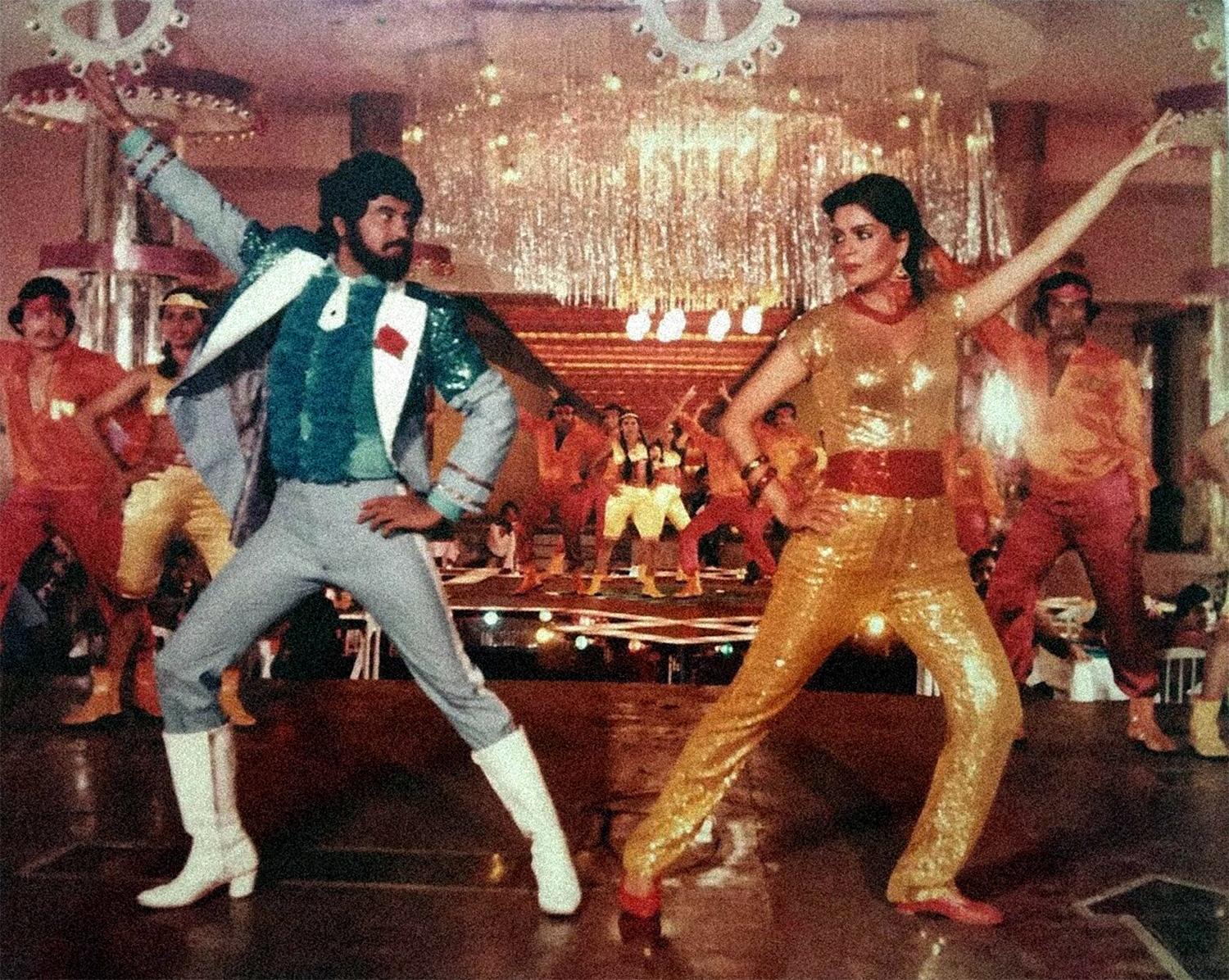

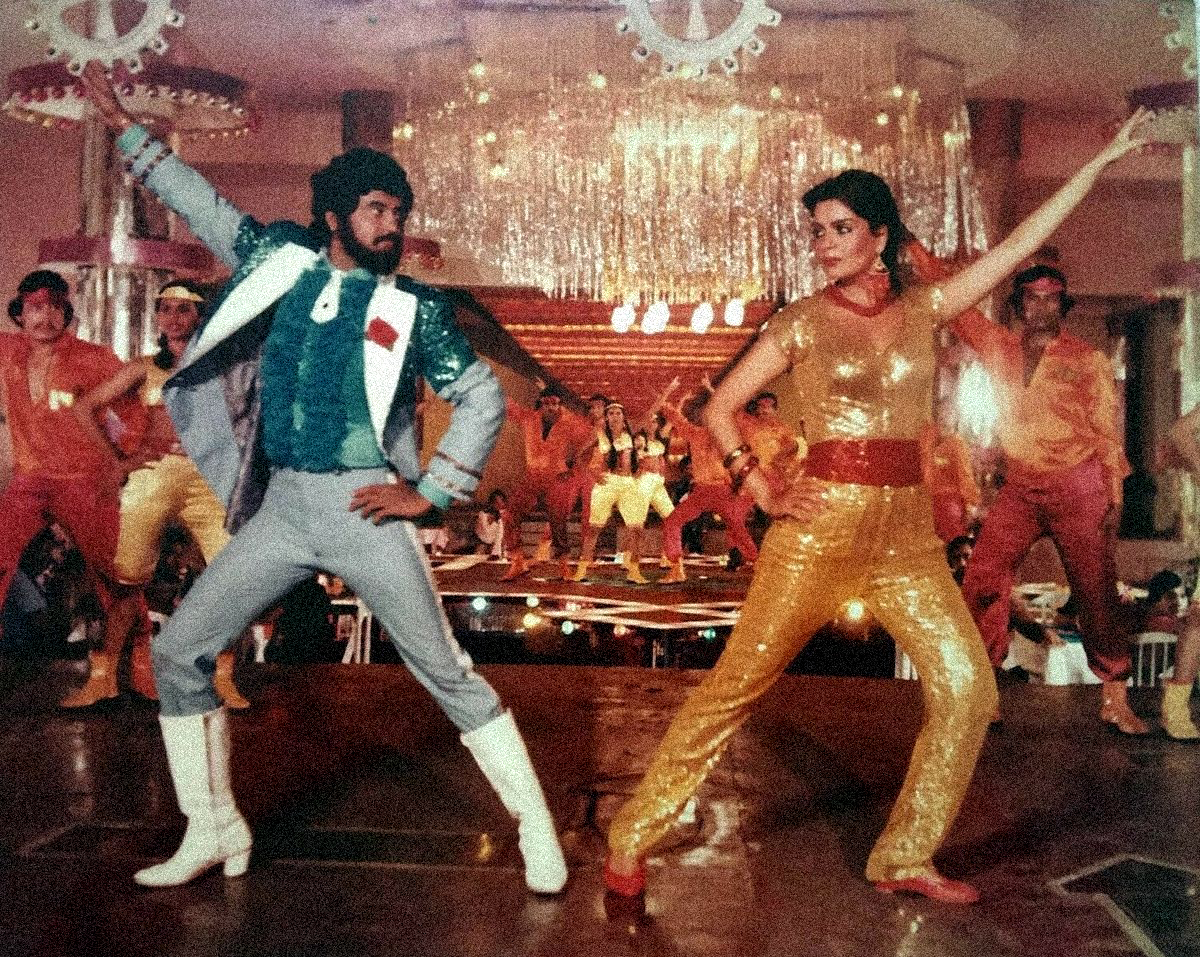

<h1 class="left">Banner: Rajnikanth and Zeenat Aman in the song ‘Osa Asa’ by Asha Bhosle and Bappi Lahiri, from the film ‘Meri Adalat’ (1984) </h1>

<h1 class="full">In the last few years, disco–a music genre characterised by its electronic, glassy sounds, reverberating vocals and use of synthesisers–has come to represent something bigger than itself: a nostalgic longing for a simpler, better time. An era in which we could be young, wild and free. The early seventies in the USA saw disco being birthed from this very quest for freedom. It was always political, a counterculture heralded by queer, black and Latino communities in a time when there were still laws against homosexual behaviour in public. Dancing was considered shameful; dancing with partners of the same sex was illegal. Amidst this emerged hip thrusting moves, bodies vibrating together, sex in bathroom stalls, exit stairwells. Disco was inherently erotic, hedonistic, centred around non-phallic pleasure and sexual liberation. Unemployment, inflation, race riots and crime was on the rise. A growing sense of disillusionment and despair ushered in the age of disco: a rebellion, a collectivist escape, a sexual revolution for outcasts.</h1>

<h1 class="full">This style of music burst into India with a 15 year-old Nazia Hassan crooning ‘Aap Jaisa Koi’ for Qurbani (1980). On screen, Zeenat Aman, a single ruby rose in her hair, swayed to the track in a sparkling bloodred cut-out dress. Hassan instantly became synonymous with the genre: in the next few years, she would go on to release smash hits ‘Disco Deewane’ and ‘Boom Boom’, both album singles, with her brother Zoheb. Both records–and ‘Aap Jaisa Koi’–were composed by Bangalore-born, London-based Biddu Appaiah, a pioneer of disco in Europe and India. In the USA, Mumbai-born Asha Puthli had long been working on genre-defying records that disco would eventually descend from.</h1>

<h1 class="full">“They were some of the key innovators of disco as we know it in the West,” reveals Raghav Mani, co-founder of Naya Beat, a label that works to revive forgotten South Asian dance and electronic music. Most notably, Naya Beat restored and reissued Mohinder Kaur Bhamra and Kuljit Bhamra’s long-lost 1982 album Punjabi Disco and are leading the revival of Puthli’s legacy through the release of remix EPs like Disco Mystic (2023) and an international tour, her first in 44 years. “In New York City, Asha Puthli created seminal pre-disco records like The Devil is Loose and 1001 Nights of Love. Biddu wound up in Europe, created the Eurodisco sound, and then brought that back with him in his work with Nazia and Zohaib. There’s a very interesting full-circle aspect to it all–these two Indian artists had a really important role to play in disco in the West, and then that was fed back into India.”</h1>

<h1 class="full">By the time disco emerged in India, it had started to fade in the West. “The Bee Gees’ soundtrack album for Saturday Night Fever (1977) was probably the height of its commercial success. Then it went back underground and eventually evolved into a kind of boogie and electro-funk,” explains Mani. There were overtones of racism and homophobia in the backlash against this genre, which was dismissed by rock music fans as superficial and shallow and vanished almost overnight. In 1979, Steve Dahl–a DJ fired from his job at the radio station because they were planning to transition from rock to disco–invited listeners to Disco Demolition Night: 50,000 showed up; crates of disco records were blown up on a baseball field. In India, however, disco remained a part of mainstream Bollywood music from the late seventies to the mid eighties.</h1>

<h1 class="full">This timing was significant. As in the USA, disco in India closely followed an oppressive political climate. The 21-month Emergency had only been revoked about two years before Bollywood’s disco fever, which was a call to liberation, cosmopolitanism and modernity: a cultural handover to the youth of the country. In his signature black sunglasses and heavy gold necklaces, Bappi Lahiri composed, produced (and sometimes plagiarised) many memorable tunes: the 1982 Disco Dancer album featuring ‘Jimmy Jimmy Jimmy Aaja’ which became a global sensation during the COVID-19 lockdown; ‘Jawani Janeman’, seductively sung by Asha Bhosle and brought to life by a gold-clad, glamourous Parveen Babi; ‘Disco Station’ , ‘Intehaan Ho Gayi’ and ‘Yaar Bina Chain Kaha Re.’ R.D. Burman refused to stay behind, composing ‘Yamma Yamma’, ‘Aa Dekhen Zara’ and ‘Jahan Teri Yeh Nazar Hai.’ Extravagant sets; flared, flowy bell bottoms to make dance easier; shiny headbands; all of Russia – where Hollywood was censored–drooling over Mithun Chakraborty in Disco Dancer. Unlike the West, where it was for those on the margins of society, Bollywood rebranded disco. It came to be associated with affluence: men in tuxedos–Feroz Khan, Shashi Kapoor–stoically gazing at women like Aman and Babi, ornamental, drenched in sequins, singing and dancing for them.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Still this subculture seeped into the crevices of India. For the masses, going to the disco became interchangeable with visiting a nightclub, going dancing. Lahiri’s experiments with synthesisers inspired composer Charanjit Singh to create Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat, accidentally inventing acid house in 1982. In the same year, diaspora albums like Punjabi Disco and Rupa Biswas’ Disco Jazz were created and largely disregarded. In his digging adventures, music archivist and record store owner Nishant Mittal has rediscovered countless obscure disco records that still remain mostly unknown: from Marathi disco and Sindhi disco to disco remakes of Indian prayers, disco-qawwali, Kannada language remakes of Hindi disco tracks, Oriya disco and more.</h1>

<h1 class="full">“The great thing about Indian culture is that if we copy, we do it in an innovative way that reflects our culture and musical heritage,” notes Mani. “So an Indian disco soundtrack had many unique elements: there was more drama, more surprises. It was disco-inspired, not copycat disco.” As new technology like synths and drum machines grew popular in India, he adds, composers like R.D. Burman, Charanjit Singh and Bappi Lahiri stuck to the West’s rhythmic elements but “replaced entire lush string sections and horn sections with presets and instrumentations on these machines. This created a compelling new sound.”</h1>

<h1 class="full">It was an era of transformation, of technological advancements that no common man could have imagined just a few decades ago. Man had now been on the moon. In the same year, musician Gita Sarabhai had introduced the synthesizer to India while her brother Vikram headed space research for the INCOSPAR. Disco urged us to look to the future; it advocated speed, technology and youth culture, inspired hope in a still newly independent India for whatever was coming. Space missions happening around the world “made humans wonder about the cosmos, the expanse of the universe and other living beings on other planets”, observes Anusha Vikram. This manifested not only in the futuristic, mechanical sounds of disco–laser, buzzy noises akin to spacecrafts–but also in the cosmic, almost dreamlike album art and lyrical themes accompanying this music. Take Nazia and Zoheb’s Star: a singer, lit by starlight, poses against the vast night sky. Disco Dancer (1982), Armaan (1981), Zamaane Ko Dikhana Hai (1981), all featured near-celestial beings against beaming lights.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Unlike the West, disco died quietly in India, replaced by other genres and styles of production like Indian pop. Occasional tracks in the 2000s–‘It’s the Time to Disco’ (2003), ‘Aaj Ki Raat’ (2006), SOTY’s ‘Disco Deewane’ remake (2012)–paid homage to the genre. But soon we realised that technology had failed to create the utopian world we had imagined it would, and this aesthetic, along with everything it represented, disappeared across the globe.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Except: only two weeks ago, Harry Styles announced his upcoming album: Kiss All the Time. Disco, Occassionally. More importantly, previously overlooked trailblazers are unexpectedly gaining the recognition they deserve: Charanjit Singh’s Ten Ragas to a Disco Beat is now almost mainstream, set to be reissued by American label Light in the Attic Records in June 2026. Punjabi Disco’s overwhelming success 44 years after its release has surprised and overwhelmed Kuljit Bhamra who notes the youth’s “renewed interest in the physical nature of listening to music and exploring how it’s been put together.” At the age of 69, Rupa Biswas released her second record since Disco Jazz and performed live for the first time in 30 years. At 70, Asha Puthli’s global tour is selling out. What to make of this return of disco except that it always seems to return when we need it the most? In times when government control tightens, censorship grows and fascism slowly rises. Disco, art, resurfaces, mixed with rebellion, with a quiet surge of hope. Inexplicably, we find ourselves gravitating towards the age-old ways in which we fought back, towards the impulse to reach again for the stars. Inevitably, history repeats itself. Inevitably, disco lets us escape. But more crucially, it helps us unite: to sing and dance again under the glitzy lights.</h1>

<h1 class="full">Banner: Rajnikanth and Zeenat Aman in the song ‘Osa Asa’ by Asha Bhosle and Bappi Lahiri, from the film ‘Meri Adalat’ (1984) </h1>